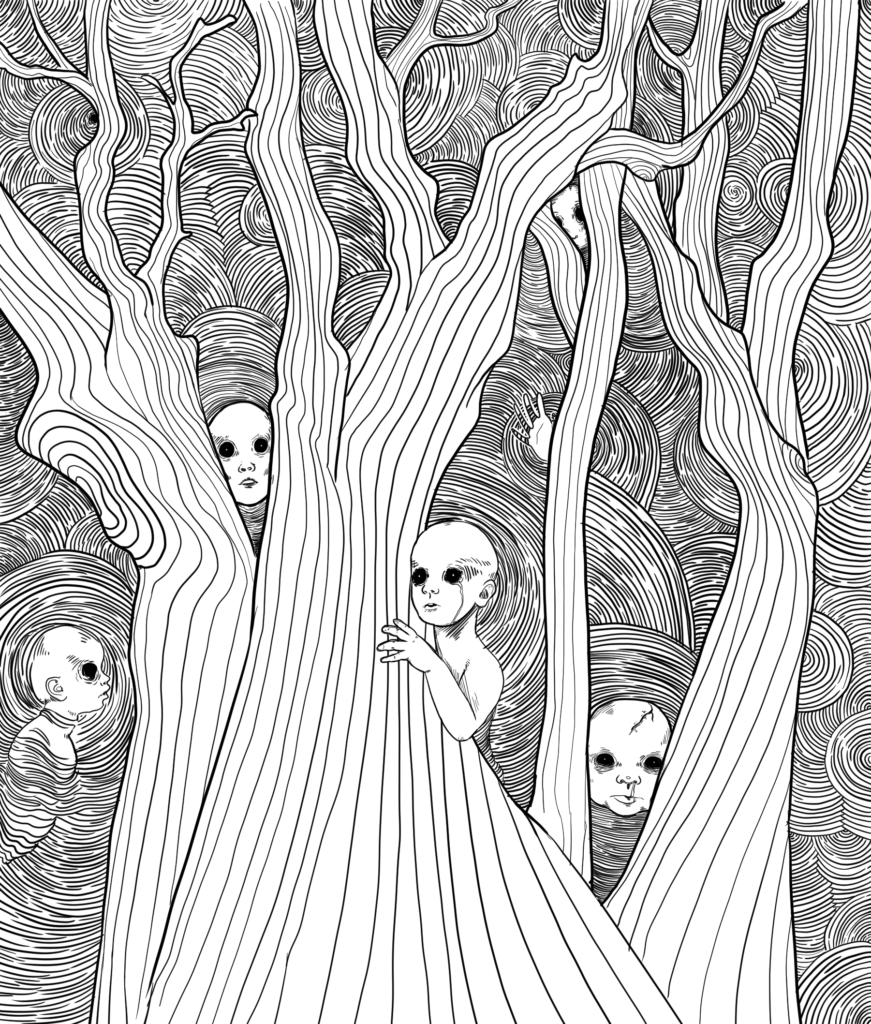

Norse mythology and folklore feature plenty of creatures who lurk in the woods, ready to lure people in.

What most of them have in common is that they are not from the human world, nor have ever been a part of it—they come from the magical realm, or the world of the dead. There are a few exceptions, however, and among these are the mylingar. Not only have they once been part of the human realm, if only for a brief moment, but they also have the saddest story behind why they were turned into creatures of the night.

Mylingar are ghost children—often children born of non-matrimonial relations between a man and a woman that resulted in an unwanted pregnancy. Since a woman would be an outcast in society from the Middle Ages up until the 20’th century if she had a child outside marriage, many women had no choice but to end their babies’ lives as soon as they entered the world. This was a terrible sacrifice for the woman, surely something they did not want to do, but were left with no choice as having a child outside marriage was punishable. Therefore, it was not an uncommon practice to dispose of unwanted children—in fact, early Norse Christian law codes make a specific prohibition of this practice, which indicates this was truly an issue in society. Before we judge too harshly, we must understand that times were far different to our own, and a worse life might await both the child and the woman if she were to keep it.

The child would be buried someplace the mother could hide it, like a bog, in the forest, or even underneath the floor or in the attic of a house. The child, who died unbaptized and not buried in holy soil, would become a ghost—a myling—and in the night one could hear the child’s cries from its burial ground. Some say that the child would cry for as many years as it would have lived if not killed. Sometimes the reason the child would make so much noise was so that it could be found and be buried in holy soil and get some peace. Other times the myling would call out for help, asking to be given a name, as it was never given one in life. To then give the myling a name was another way of saving it.

However, mylingar were not only sad children in the night. Some of them were rather vengeful, and could bring both disaster and death in their path. Mylingar were known to try to reveal who their parents were, both mother and father, by singings songs of the terrible fate they had suffered. The child could also seek its mother and nurse her to death by drinking her blood trhough breastfeeding. A myling could also suddenly appear on its mother’s wedding day—when the wedding dance had started, a ghastly voice could be heard underneath the floorboards saying, “vessels are narrow, legs are long, and I want to dance once again”. The child would then rise from the floor and take its mother to dance until she died of exhaustion.

Less is known of the father’s punishments, and mylingar are an echo of the unequal blame women have received throughout ages when it comes to childbirths and unplanned pregnancies.

If it were sufficiently vengeful, a myling might not only be after its own parents, either. In some parts of Scandinavia, such children are said to be lurking around streams and brooks, where they call out to other children. If any child should answer the calling, the myling would then drown the unwitting child so it could have a playmate forever.

Mylings could also appear as the less common nattramnar—children killed in the same way as mylings, but turning into ravens instead of ghosts. Nattramnar only show themselves during the nights, always flying from west to east, and quite specifically, never closer to the ground than the height of an ox. On its flight it would utter creaking sounds, as from an old wagon wheel.

So, when you hear a child cry in the woods at night, or by your outhouse or underneath the floor planks of your house, make sure to have a name close in mind. And beware of streams and brooks after nightfall.

Cover Illustration: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Text: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.