While Thomas was at work on April 8, 2021, drawing maps for orienteers in a forest outside Alingsås, Sweden, he stumbled upon what turned out to be one of the biggest Bronze Age finds in Sweden.

Thomas just had made his way through some dense brushwood when he spotted what, at first glance, he thought was a lamp. As he stood on top of a stone pile close to a mountainside and looked around him, he noticed bronze objects scattered around the ground underneath him.

It turned out to be jewelry, all in near-pristine condition. In fact, they were in such great shape that Thomas started to look for stamps of authenticity, such as modern jewelry would have, but could not find any. Upon closer inspection, he slowly realized that this might be something far older that he initially thought.

When archaeologist Mats Hellgren arrived at the site, he was astounded as well over the great condition of the items, given that most Bronze Age finds tend to be quite fragmented.

“I almost thought it was modern day copies,” Mats said at a press conference later.

What came to be uncovered when archaeologists arrived is one of the greatest finds from Sweden’s Late Bronze Age (700-500 B.C.). It is unique in several ways: not only the vast number of items and how well preserved they are, but also the place they were found, and that they were a deposition—items deliberately placed, rather than being lost or forgotten.

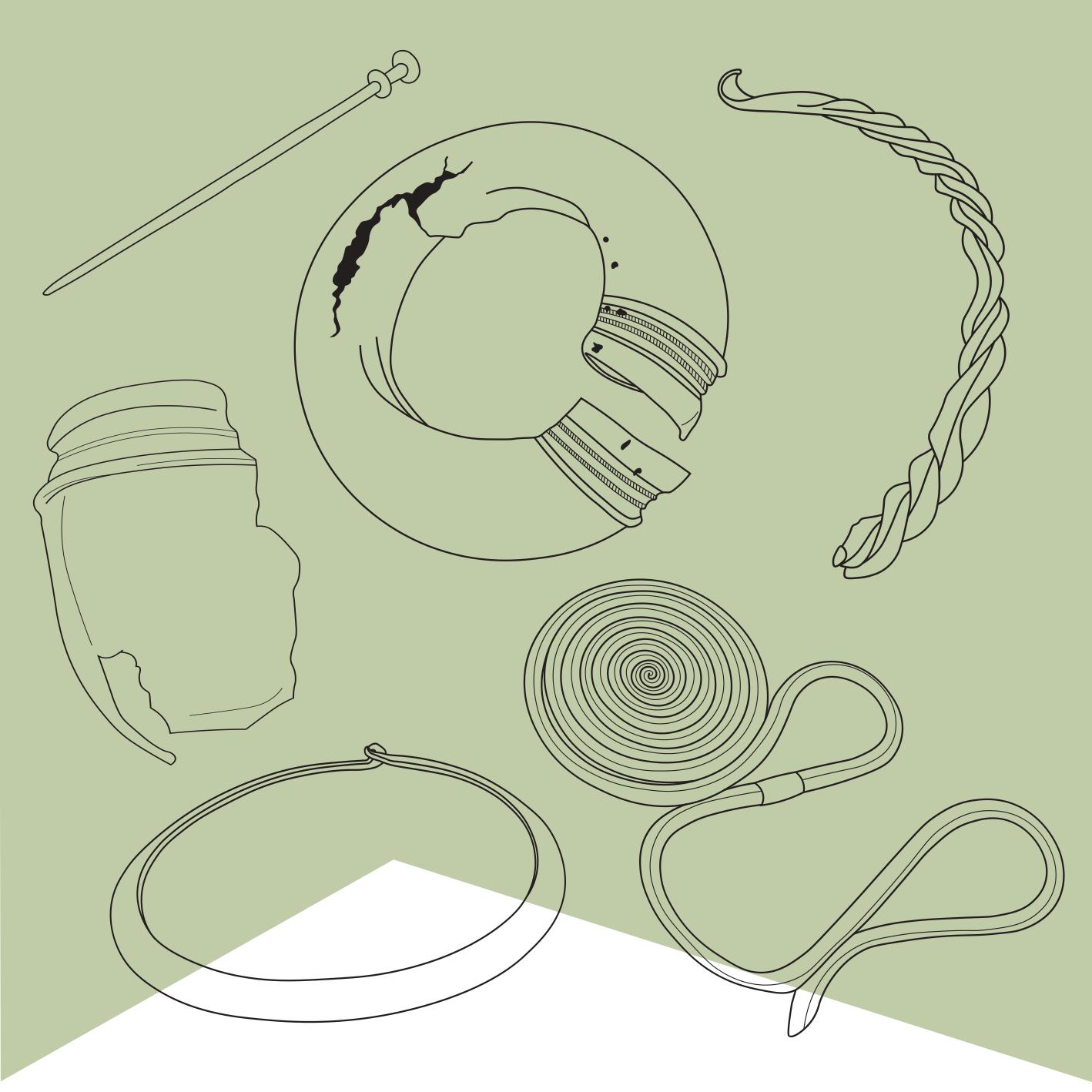

On April 29, the county administrative board inVästra Götaland (the county where the bronze was found) held a press conference about this new and exciting find. All in all, the find consists of about 50 bronze objects, amongst which neck rings, foot rings, dress pins, and an axe can be found. Most of the objects had likely once belonged to one or several high-status women.

“They were used to mediate a woman’s social and exclusive status,” explains Johan Ling, professor at the University of Göteborg.

As this was a unique find in terms of Bronze Age deposits, the decision was made that an archaeological survey should be conducted immediately. The site, consisting of a pile of stone boulders, was quickly secured by archaeologists and they began to excavate. About 80% of the items were found scattered around in front of the pile. The reason? It seems an animal had been working hard to build a burrow amongst the stones, removing all loose items in its way in the process. And in this case, we were lucky it did, otherwise the treasure would still not have been found.

The remaining 20% was still underneath the largest boulder in the pile. This made it quite hard for archaeologists to reach the items, but they managed to remove stones from the back in order to get the last pieces out.

The reason why the items are in such exceptional condition was explained by conservator Madelene Skobert. The items have been well preserved because the composition of acids in the ground at the site has stayed consistent from the time of deposition to the present day (in other words, for over 2500 years!). As a result, the decomposition process had not started with the items as it normally would have.

When archaeological sites of this sort are found in Sweden, it is important to do a proper archaeological survey for two reasons: firstly, to document the traces of the find, as well as the event when the items were deposited 2500 years ago; and secondly to investigate if there are any more items in the area.

“We want to know more about who made the deposition, when it was made, and why that place in particular was chosen, as well as why the deposition was made?” says Pernilla Morner from the county administrative board. “Was it done in order to hide the items, or was it perhaps a sacrifice?”

“In the long run,” she continues, “it is about finding out how life could look like for people who lived in our part of Sweden during the Bronze Age.”

The find is unique in many ways. It is not only one of few depositions from the Later Bronze Age that ever have been discovered, it is also the only one of its type that has been investigated with modern archaeological methods and technical approaches.

Professor Johan Ling explains that depositions from the Bronze Age have been investigated before, during the 19-20th century, but that the excavations, or digs, had been done by laymen. As a result, the contextual data tend to be few, or non-existent.

The survey started with photography as the first step, including photogrammetry (a way to measure 3D positions of an objects), drone pictures, and laser scanning of the site. The site was then excavated, and the finds were digitally measured and laser scanned on site, meaning it is possible to rebuild the entire site in 3D later on and make an exact reconstruction of where the items were found.

Macro samples (microscopical biological remains such as pollen and seeds) were also taken from the site, which can reveal if certain changes occurred at the site during the time for the deposition; for instance, they could show if there were any climate changes.

Macro samples can also help with the dating of the site. Mats Hellgren explains there is a possibility though, that samples might not be valid as animals can have contaminated the area.

Archaeologists have also searched the area with a metal detector, something that is illegal in Sweden unless done by professionals. Due to the use of the metal detector, all finds could be recovered, otherwise some items can easily go undetected. Surrounding areas have been surveyed as well, but no trace of human activity could be spotted. The site for the deposition has no clear connection to other places with settlements or graveyards in the area, and therefore, future research will try to establish why this spot was chosen for this rich deposition.

The excavation also had conservators (experts in the art of object conservation) on site, a decision that turned out to be a good choice given the complexity of the site and difficulty in retrieving the items. The perks of having conservators on site are that they can pick up the objects themselves, and they can see the items in situ (on site) which helps them plan ahead if objects were broken, in this case the foot rings. It also gives them an overall advantage later on in the lab, Madelene Skobert explains.

The items will go through a conservation process which, first of all, will make them less susceptible to degradation, but it can also enable researchers to see decorations that have faded over time, traces of use, damage, repairs, and traces from manufacturing, among other things.

Regarding further research, this find will open a lot of new directions.

Johan Ling explains that the type of landscape in which the items were found in is a new pattern and that creates completely new research questions. Since it was a deposition that was found, new questions need to be asked to this place and if more depositions can be found.

The question of deposition has a long history of research and interpretation behind it. Why depositions were made is unknown, but there are theories. One possibility is that it was a treasure hidden in times of war for safe keeping. This theory does not always hold though, as the treasure would reasonably be expected to have been dug up again, unless off course, the person or persons were killed.

A theory that finds support from more researchers is that it was a way for groups of people to demonstrate their power and social status to other groups. The deposition would function as a display of wealth, by showing off one’s ability to sacrifice valuable items.

It could also be a sacrifice made during a funeral, with the body buried elsewhere from the belongings. The thought was that the dead would use the items in the afterlife, despite not being buried by the body.

The amount and exclusivity of the items enables a variety of questions to be raised, regarding the individuals who made the deposition and the society they lived in?

The type of foot rings that were found have only been discovered twice before in Sweden, and even then, in a highly fragmented state. However, they are rather common in northern Germany and Poland, leading to the conclusion that the person or people who deposited the items must have had some sort of connection to the continent.

“Overall, this shows that we need to direct a lot more research to a find like this,” Johan Ling says.

A number of different analyses will be conducted, one of which will be a metal test to determine where the copper and tin (the constituents of bronze) came from. The items will also be conserved, and the National Heritage Board will decide which museum will be given the honor of displaying the items.

Before, finds of this type would be given to the National Museum in Stockholm, but now regional interest is considered too, Pernilla Morner explains.

The heritage board will also estimate the value of the items and give a finder’s reward to Thomas, the lucky mapmaker.

We at Scandinavian Archaeology are truly looking forward to all the new research that will be made due to this find, and we can not wait to tell you more about it!

Cover image: Lovisa Sénby Posse 2021. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Text: Lovisa Sénby Posse 2021. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

You can see the press conference here:

(It is in Swedish)

https://www.vgregion.se/kulturutveckling-direkt

To read more, or to contact the researchers:

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.