The Iron Age is the third and final period of Christian Jürgensen Thomsen’s “Three Age System”, following the Stone Age and Bronze Age. The age is mainly marked by the production and mastery of a new metal: iron. This new product fit well into the changes and development occurring in Scandinavian society, contributing to new trades and industries while bolstering the already-established warrior class as stronger and more durable weapons emerged. The Nordic Iron Age, a period of about 1600 years (c. 500 BC-1100 AD), saw massive change in Scandinavian society in the realms of economy, culture, and politics, but also in the landscape of people as large-scale migrations of the native population took place. Late in the Iron Age, a huge natural disaster devastated much of the Scandinavian population, contributing to another great upheaval of Nordic society and leaving an indelible mark on its mythology, possibly birthing the myth of Fimbulwinter and influencing the tale of Ragnarök. It was also a time of new worldly discoveries for the Scandinavians, both during the great migrations in the middle of the Iron Age and, of course, the famous voyages of the Vikings at its conclusion.

The Nordic Iron Age is generally divided into five sub-periods: the Pre-Roman Iron Age (c. 500 BC-0 AD); Roman Iron Age (c. 0–375 AD); Migration Period (c. 375-550 AD); Vendel Period (c. 550-750 AD); and Viking Age (c. 750-1100 AD).

The beginning and the production of iron

At the beginning of the Iron Age, the Scandinavian population had been farming for well over 3500 years. During this time period, farms grew larger than ever before and some of them eventually became the centres of places of great regional power. The famous Scandinavian longhouse developed, which became homes for entire extended families as well as their animals, who were now kept inside during the winters to help keep the large buildings warm. A changing climate was partially behind this, as weather conditions were changing rapidly and winters becoming colder.

The beginning of the Iron Age is, of course, also marked by the large-scale production of iron. The rapidly growing population in Scandinavia needed a larger source of income, and iron, discovered in the bogs, opened up new opportunities for them. Iron was a difficult metal to master: unlike stone it was unworkable in its raw form, and it required far greater temperatures to smelt than copper and tin. But once the breakthrough occurred, the new types of new tools that iron could produce changed the landscape completely. Moreover, iron could be produced locally, which was more practical than importing bronze or its raw components.

It is no surprise that iron came to rapidly replace both stone and bronze in the ensuing years, as it offered numerous advantages over these materials. It made for weapons and tools that were more precise and effective, and became an important factor for warfare, hunting, and fishing in Scandinavia. It also lent itself to sturdier agricultural equipment—importantly, ploughing the soil became an easier task requiring far less labour. Iron could also, crucially, be used to make sturdy nails and rivets, and with these, greater ships could be built; now, more Scandinavians could travel abroad to strengthen political and economic interests. This, in turn, led to more people being able to obtain wealth than ever before.

Adding to this effect, around the end of the Pre-Roman Iron Age, silver became a new and valued commodity in Scandinavia. This set the stage for enormous changes centuries later in the Viking Age, which became a sort of “Age of Silver”, when it became the metal of currency and a symbol of status and power.

Distinct power structures had developed during the Bronze Age and much of this system remained intact throughout the first half of the Iron Age. But during the Vendel Period), these structures began to change again, with more levels of hierarchy in society and increasing inequality between them.

The Scandinavian structure

Scandinavia was divided into a number of “territories” during the Iron Age, each said place with a small ruling elite at its head. These territories had a great deal in common with one another culturally, although the people within each territory had their own distinct norms, rituals, and rules that they followed. However, these territories were not defined by geographical borders; rather, they were largely based on political and social relationships (they were spheres of influence, not bounded countries). They were fluid in their scope: it was very likely that people often changed their preferred territory by shifting their loyalties between leaders, which resulted in the opportunity to change one’s social status and led to mixture of populations.

Throughout the Iron Age, there was an ever-increasing contact between Scandinavia and other European countries, including the Roman Republic and later Empire. This increased contact can be seen in the vast archaeological material from this period, which indicates not only the great ability for trade, but also an increase in Scandinavian raiding on the continent. Items acquired through import often became what archaeologists call “prestige objects”, bringing status to their owners (in this case because of their exotic nature), which created a larger difference between poor and rich during the Iron Age. Amplifying this, unfortunately, was the introduction of slavery to Scandinavia on a far larger scale, with foreigners either purchased or captured abroad by Nordic travellers to be brought north. The inequality is especially visible during the Vendel Period (c. 550-750 AD), when the gap is believed to have been the largest. The Vendel elites were people of truly immense wealth, but they represented only a tiny fraction of the society and their wealth was largely kept “in the family” by inheritance. During the Viking Age (c. 750-1100 AD) the playing field became more complex, with more variable levels of richness and status becoming visible as trade and raiding allowed people to obtain power without having to inherit it as before.

Wealth expressed in burials

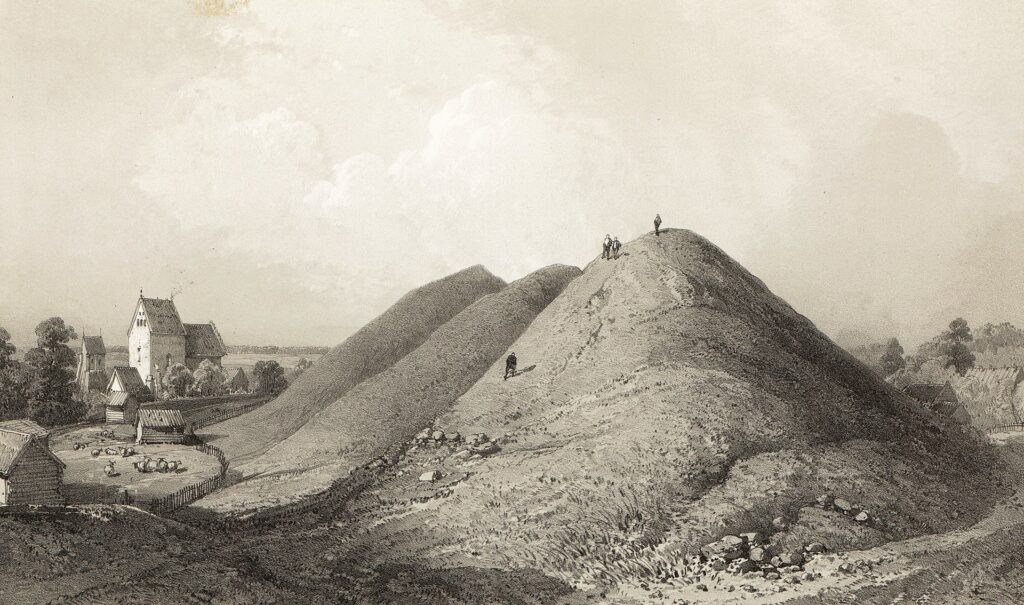

Human culture is always changing, but the Iron Age is likely one of the first prehistoric periods when this change was truly constant, morphing faster than ever before. This can be seen in the ever-growing differences between the wealthy and the less fortunate, something that often foreshadows an approaching shift of power in a society. This gap only became larger after its emergence during the Bronze Age and becomes evident in the last vast variations in burial practices across Scandinavia, where some of the graves are so rich that they can barely be comprehended by a modern society’s funeral standards. These extravagant grave practices had their peak during the Vendel Period, after which a more “bourgeois” approach to burial developed during the Viking Age, in line with more levels emerging within the society’s hierarchy.

During the Iron Age, there were many different funeral traditions, varying by time, place, status, socioeconomic factors, gender, and belief system. Most common was cremation, while others might have been buried in boats, buried in mounds, in so-called “chamber” graves, or in simple pits without any markings at all. The vast differences in burial practice during the Scandinavian Iron Age can often be confusing and misleading. The idea that everyone was buried in great, rich mounds is false: these mounds represent only a small part of society who lived extravagant and rich lives. Wealth in such burials might have been expressed through the extravagant clothing, jewellery, glassware, ornaments, and weapons and armour (some beautifully decorated, gilded, and bejewelled), but also sacrificed animals and even humans. This variability gives archaeologists a good indication on the scale of differences in wealth during the Iron Age, and burials are therefore among the most valuable archaeological discoveries of the Iron Age.

Migration and raiding

As its name suggests, the Migration Period (c. 375-550 AD) saw large migrations of Nordic populations within Scandinavia and out of it, as part of a broader European phenomenon of migrating Germanic “tribes” (in the Classical arena, this is often referred to as the “Barbarian Invasions”). Pertinently, three Danish groups—the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—spread across the North Sea to Britain where, over centuries, they became the “English” people or Anglo-Saxons; another famous people who may have connections to Scandinavia, particularly southern Sweden, are the Goths, who spread west, south, and east across the European continent.

But raiding is likely, for better or worse, what this time period in Scandinavia is most known for, and it undoubtedly produced a lot of newfound wealth in the Scandinavian world. Men and women could, to a larger extent than before, make a name for themselves by their talents in warfare: either serving in powerful families’ private retinues, signing up as mercenaries with powerful societies on the continent, or going out and seeking their own fortune. The Viking Age is likely the sub-period during the Iron Age that is most known for its raiding and warfare, but warfare had been endemic in Norse societies by centuries, evolving out of the “warrior ethos” that developed in the Bronze Age.

Understanding the agendas of war and warfare may diversify our view of the so-called “warrior Viking”. Perhaps they were not only bloodthirsty pillagers lusting for violence, but rather complex and dynamic individuals, capable of pursuing a multitude of different agendas and adapting to different situations. Thus, being a warrior may be understood as only one aspect of a person’s fluid and ever-changing identity, but it was clearly one of the more significant things a person could “be” during this time—if the large number of swords and other weapons in graves are anything to go by. The centuries of raiding in the British Isles and Frankish Empire, who made these events a permanent part of their historical canon, has also undoubtedly contributed to this image.

Archaeologists and historians alike have done extensive research in identifying the economic, political, and cultural factors that led to the migrating Scandinavian population during the Viking Age. Overpopulation of Scandinavia was an old explanation that has largely now fallen out of favour, as has the old idea that Vikings were pagans motivated by their hatred of Christianity.

Social, cultural, political, and economic aspects are often valid reasons behind migrations, and surely some of these were at play. Land hunger caused by over-farming and climate change might have put pressure on families to pack up and emigrate, leading to the age of Viking colonisation. In the early Viking Age, the level of social inequalities might have led people to try their chances out in the world instead. But matters of the heart (or other body parts) may also have played a surprising role. Some researchers argue that it was the effect of the institution of “bride price”, where a man who wished to marry a woman needed to pay a certain sum to her family, that caused so many young men to go hunting for fortune. On a not-unrelated line of thinking, it has been suggested that selective female infanticide had led to a skewed ratio of males to females, with wealthier men practicing polygyny and concubinage, forcing young men to go abroad to find “mates” there instead.

But on a more basic level, the desire for prestige and wealth, fame and power, could also have been reasons for the migrations and the raiding—as stories of war, exploration, and the exotic spoils of these efforts could bolster a person’s status at home. Furthermore, a connection between Scandinavian religion and the warrior mentality could have been a motivator for pillaging.

But historical trends are never one-note, and it is reasonable to assume that some, or all, of these motivations played an important role in the Viking raids and settlements.

Trade, and marriage, and mercenaries

But raiding was not the only way the Scandinavians obtained riches. They were also skillful in the art of trade, and Scandinavia had a lot of wares to offer. To begin with, Scandinavians were extremely skilful craftsmen in a variety of media—most visibly their metal production, but also distinctive textile and woodworking, though these do not preserve as well. With these products, but also valuable raw materials such as furs, lumber, honey, and amber, the Scandinavians gained great wealth through trade. The “Swedish” Vikings travelling along the rivers of Eastern Europe are most famous for this, and the Swedish island of Gotland became a nexus of trade in Europe.

But this was not the only way to strengthen one’s standing in the world. Marriage between, or into, powerful families has always been an avenue to power and wealth. For instance, the great burial of Sutton Hoo, England, contains distinctively Scandinavian treasures that are believed to attest to a marriage between an English king and a Swedish princess.

And lastly, another famous way to gain wealth and power was through mercenary work, a tradition going all the way back to the Roman Iron Age. Grave finds and Roman chroniclers suggest Scandinavians would travel south to the European continent to serve as mercenaries for the Roman army, bringing prestigious and valuable treasure home after their service. Later, Swedish Vikings formed the “Varangian guard” of the Byzantine emperor, and Vikings from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden were hired to fight on behalf of the Franks, English, Irish, and Byzantines.

Runes

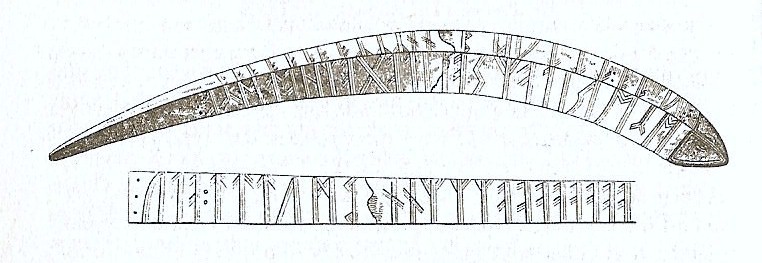

The famous runes were also developed during the Iron Age. Runic inscriptions can be found, most famously on stones, but also on other places, such as walls, burials, and items. The first known inscription in stone dates to 350 A.D., but carvings on wood, metal, and bone artefacts predate this by centuries. The Elder Futhark is the name of the earliest runic script, most evidence of which is found in Denmark; the Younger Futhark developed in several local forms over the Viking Age, and the vast majority of these inscriptions come from Sweden.

Runic inscriptions are not only found all over Scandinavia, but even some of the places they visited overseas bear markings: famously, the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul was “autographed” by a certain Halfdan. Runes are the first preserved written record in Scandinavia, and testifies to lives lived and lost, and as such they are some of the Iron Age’s most personal heritage.

A new religion, a new power, and a new era

Several factors led to the development of the Iron Age society into the society of the Middle Ages. Firstly, Scandinavian rulers had fashioned themselves in the likeness of European kingdoms and made themselves major players on the European continent. A second development was the adoption of a monetised currency economy, evolving from a barter-and-trade system, to a system based on weighted silver, and finally through to a fully modern coinage system. Thirdly, by the end of the Iron Age, the Scandinavian world had largely converted to Christianity, which made it part of the broader European cultural and political scene, facilitated its relationships with other European kingdoms, and centralised and bureaucratised the Scandinavian rulers’ wealth and power. The shift to Christianity was not always violent nor peaceful, and seems to have varied regionally. However, it does seem to have been in general more welcomed by women than by men, whose position in many ways benefitted from the new religion.

Summary

The Iron Age was a period of rapid change and a growing society facing many setbacks, but also a lot of development. As a new metal technology emerged, new tools were created which would help to streamline agriculture and trade. This in turn led to a growing population and the need for expansion, but also migration, and this often led to warfare. The growing wealth was clearly marked in the landscape through burial mounds to display power, many times furnished with lavish grave goods and even ships. Exotic items were gained trough trade and raiding, and the craftmanship of the Scandinavians helped to expand trade and income. The Iron Age was a period of vaster gaps between rich and poor than had ever been seen, but later came to display diversifying levels of societal positions at the end of the era.

Scandinavian society was now more complex than ever before, and it would soon begin its transition into what we like to call “modernity”—but to get there, it had to pass through the Middle Ages.

Cover Image: Ola Myrin / Malmö Museer.

Text: Martine Kaspersen, Lovisa Sénby Posse and Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2022 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Literature

Ashby, S. 2015. What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration. In: Archaeological Dialogues 22(1). pp. 89-106.

Baug, I., Skre, D., Heldal, T., & Jansen, Ø. J. 2019. The beginning of the Viking Age in the West. In: Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 14(1), pp. 43-80

Diaz-Andreu, M., Lucy, S., Babic, S. & Edwards, D. N. 2005. The Archaeology of Identity: approaches to gender, age, status, ethnicity and religion. London & New York: Taylor & Francis.

Eldjàrn, K. 1984. Graves and grave goods: survey and evaluation. In: Fenton, A & Pàlsson (eds.) The Northern and Western Isles in the Viking World: Survival, Continuity and Change. Donald: Edinburgh. pp. 2-11.

Gilchrist, R. 1999. Gender and Archaeology. Contesting the past. London: Routledge

Hedeager, L. 1992. Danmarks Jernalder. Mellem stamme og stat. Esbjerg: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Hedenstierna-Jonson, C. 2020. Warrior Identities in Viking-Age Scandinavia. In: Aannestad, H. L., Pedersen, U., Moen, M., Naumann, E., & Berg, H. L. (eds.). Vikings Across Boundaries: VikingAge Transformations–Volume II. Routledge

Meskell, L. 2007. Archaeologies of identity. In: Insoll, T. (eds.) The Archaeology of Identities, a reader. London & New York: Routledge.

Moen, M. 2019. Challenging Gender. A reconsideration of gender in the Viking Age using the mortuary landscape. Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo.

Olsen, B. 2010. In Defense of Things, Archaeology and Ontology of Objects. AltaMira Press: United Kingdom

Vedeler, M. 2018. The Charismatic Power of Objects. In: Vedeler, M., Røstad, I.M. &

Glørstad, Z. T. (eds.) Charismatic Objects. From Roman Times to the Middle Ages. Cappelen Damm AS: Oslo.