He is one of the most famous heroes of the ancient Germanic world. His deeds and adventures are legendary in scale and thrilling to recount. He goes by a number of names, but in the Norse sagas, he was best known as Sigurdr Fáfnisbani. You have probably heard of him, however, as Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. He gained both these names when he slew the dragon Fafnir (Fáfnisbani meaning “Bane of Fafnir”) and won the serpent’s legendary treasure hoard. His legendary life has been told for centuries and his story must have been of great importance as it has been immortalised in several ways, not only trough writing.

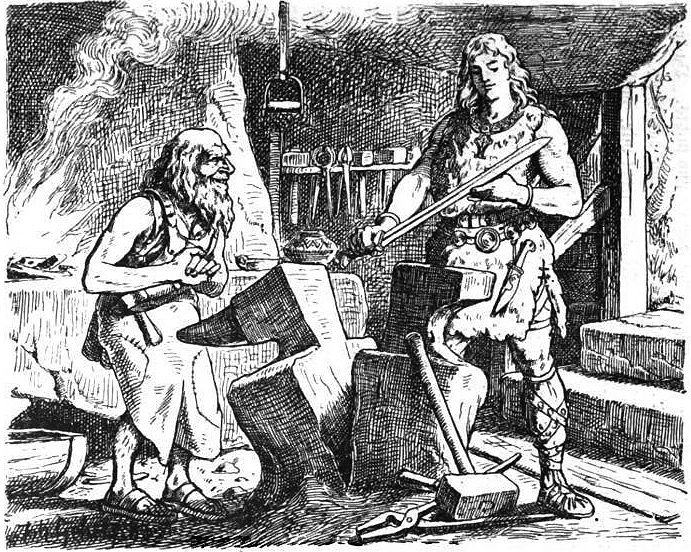

Sigurd’s life truly was a remarkable one. He was educated by a blacksmith of royal blood named Regin, who may have been one of the dwarves. He had a horse named Grani, a descendent of Sleipnir gifted to him by Odin. He inherited his father’s sword, Gram, with one small problem: it was broken. Regin offers to reforge his sword if he will partner with him in an adventure: to venture to the lair of the dragon Fafnir, who guards an incomparable treasure hoard, which they can split between them after Sigurd slays it. Regin also reveals that Fafnir is his own brother, transformed into a dragon by his greed. Sigurd agrees to the venture, and with Gram reforged, they set out. Sigurd, of course, slays the dragon, and that night, he roasts the beast’s heart over the fire for food. When he tastes its blood, he gains a new ability: he can understand the speech of birds. They tell him that Regin, who is currently sleeping, plans to kill him and keep the treasure for himself. Sigurd beheads the treacherous smith before he can awaken, and departs with a great enough share of the treasure to make him one of the richest men in the world—unfortunately, however, he takes with him a magical ring which is cursed to bring death to whomever owns it.

Throughout his life, Sigurd encounters Valkyries, awakening both form an eternal slumber, learning runes from one (Sigrdrifa) and rescuing the other (Brynhildr) from a prison of fire (there ae some debate if they are the same Valkyrie). He forges bonds of blood with mighty princes, and becomes the most famous warrior in the world. Alas, he is ultimately betrayed by his blood brothers and murdered in cold blood. Brynhildr is so distraught by his death that she commits suicide so that she might travel to the afterlife alongside him. As to his legacy, his daughter was Aslaug, the future wife of Ragnar Lodbrok and mother of many of his illustrious sons.

Sigurd has cast a long shadow through the centuries, his tale firing the imaginations of countless storytellers after him. These deeds are recounted in several of the Icelandic sagas (notably the Saga of the Völsungs) and the Poetic Edda. But he features also in German stories, under the name Sigfried (who may, actually, predate the Norse version), and in folk songs of medieval Scandinavia. Later, the composer Richard Wagner wrote an opera about his legend, calling it Der Ring des Nibelungen (the Ring of the Nibelung), featuring what would become one of the most famous pieces of music ever composed: the Ride of the Valkyries. And if all this talk of cursed rings, broken swords being re-made, dragons guarding colossal treasure hoards coveted by dwarves is reminding you of a certain author named J.R.R. Tolkien, you may rest assured this is not for nothing.

So Sigurd is, to keep it short, kind of a big deal.

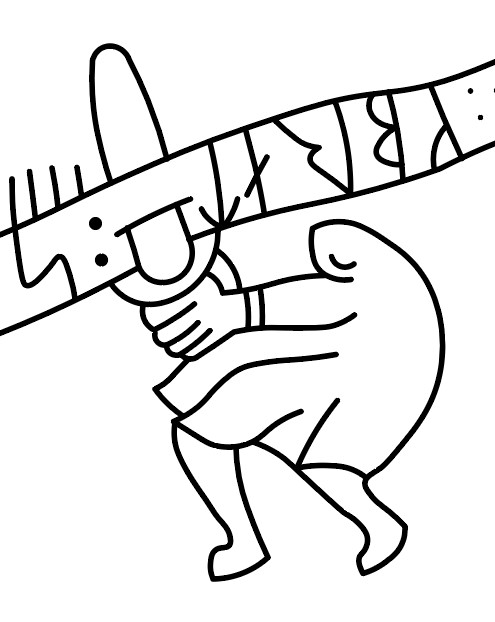

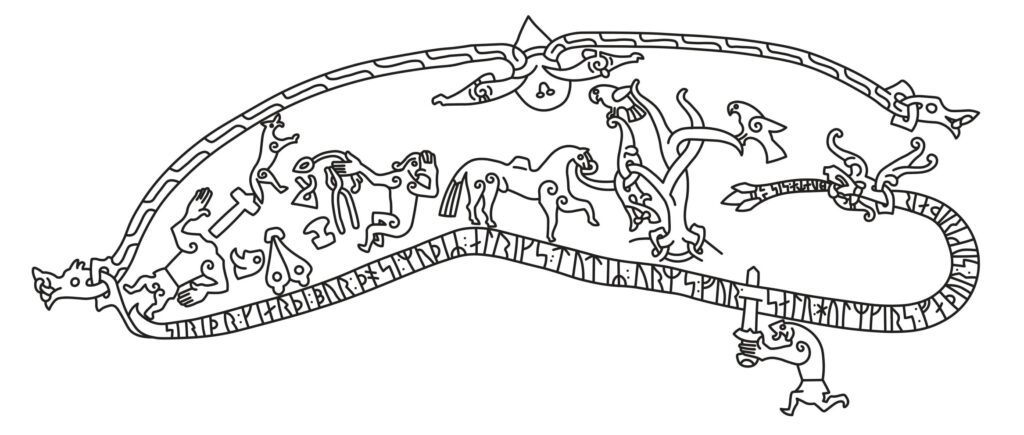

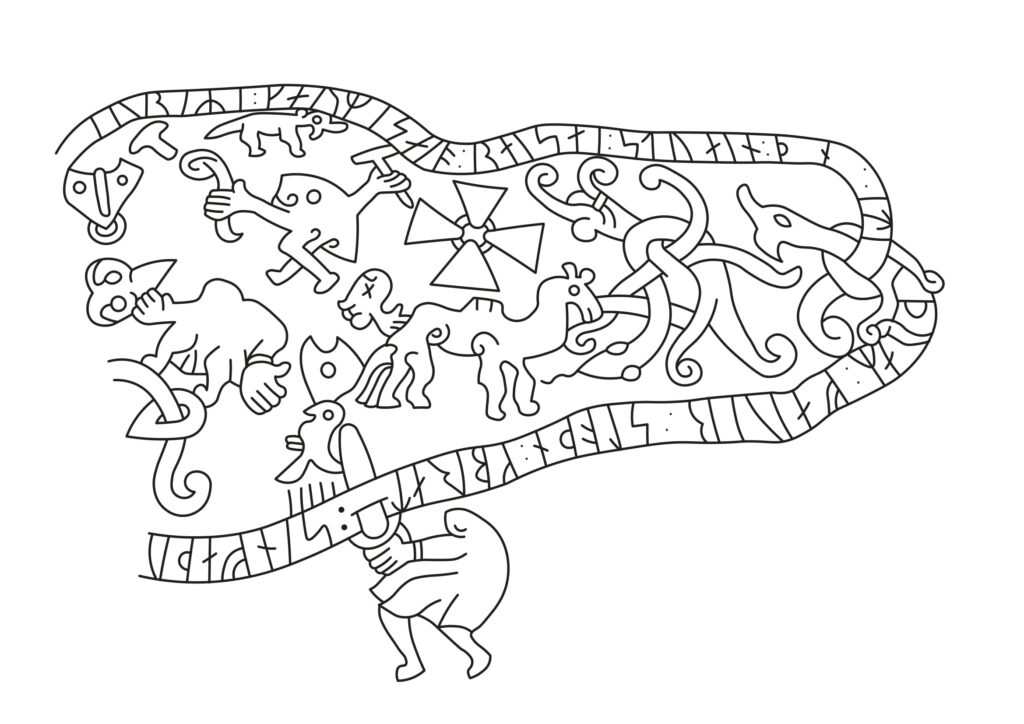

Beyond books and songs, Sigurd’s stories were depicted on several different mediums in ancient Scandinavia and Britain. Hanging tapestries, carved church doors, carved stones and slates in Britain, one Gotlandic picture stone, a baptismal font, and a stone cross all testify to his deeds. But beyond these, there is one further medium where his saga can be seen taking place, namely on rune stones. Throughout Sweden, there are eight known rune stones that have been interpreted as telling the story of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. These are clustered around central-eastern Sweden, in Uppland, Södermanland, and Gästrikland, and they recount a variety of different incidents in Sigurd’s life, or elements of his legend. Some of these stones feature motifs that could, in theory, correspond to different characters or stories. Some feature Sigrdrifa holding a drinking horn, but this is a common image aside and can only be identified with this particular Valkyrie by the inclusion of other parts of the Sigurd legend. Regin is usually identifiable by his smith’s tools, especially when he is depicted decapitated. A figure seated in front of a fire surrounded by birds is also a fairly diagnostic feature. But the key, indisputable feature marking out a Sigurd stone is the humanoid feature piercing his sword through the stone’s lindworm—that is, the serpentine ribbon containing the runic inscription itself.

Contrary to what you might expect, the runic inscriptions on these stones do not actually tell the story of Sigurdr Fáfnisbani. Instead, like most other rune stones, they usually contain a dedication to someone deceased and identify both the patron of the stone and the carver of the runes. Perhaps, then, the Sigurd elements simply reflected a favourite story of the one being commemorated, or elevated the stones’ prestige with illustrious imagery. Many of these stones are extremely elaborate, and as such they were likely time-consuming, and therefore expensive, to produce. In and of itself, this fact would have made the Sigurd stones impressive monuments to any who beheld them.

The best-known example is the Ramsund carving, or Sigurdsristningen (the Sigurd carving) inscribed on a large surface of living rock in Södermanland, Sweden. The runic inscription is a dedication from a woman named Sigridr, to “the soul of Holmgeir, father of Sigrød, her husbandman.” The text is slightly ambiguously phrased: either Sigrød is her husband and thus Holmgeir her father-in-law, or Holmgeir is her husband and Sigrød is his/their son. Given the precedent established by other rune stones, however, the second interpretation seems more likely. This stone has all the key elements of the Fafnir episode: Sigurd piercing the dragon; Sigurd roasting the dragon’s heart; Grani tethered to a tree filled with birds; and finally, the decapitated Regin with his hammer lying nearby. It even features an image of Ottar, the third brother of Fafnir and Regin, in his favourite form as an otter, who died at the hands of Loki many years before Sigurd was born.

A more confusing example is Gökstenen (the Gök stone), a massive boulder containing a strange jumble of elements from the same story. Here again, Sigurd is shown thrusting his sword through the lindworm, and so this is indisputably a Sigurd stone: but the different elements of the story are not arranged in any sensible order. This aside, the stone features two additional elements. One is a Christian cross; not so strange, given that many rune stones feature a combination of both pagan and Christian elements. Harder to explain is the four-legged creature in the centre of the stone, its humped back and snake-like neck marking it out as nothing other than a dromedary camel. No version of the Sigurd story (that we know of) has any reference to a camel, and it thus seems likely that whoever was commemorated by the stone had travelled down the eastern roads into the Near East and encountered such creatures in person. Of course, this assumes that the Gök stone is a commemorative one like most others: however, the runes themselves have never been successfully translated, and so we cannot be certain of this.

In any case, the Sigurd stones (and other artefacts) establish the age of the Sigurd legend at least as far as the Viking Age, and given their widespread nature and the similarity of their elements, they show that the story was well-known and probably much older than that. Sigurd is a hero who stands proud alongside characters like Beowulf and Helgi Hundingsbani as exemplars of a golden age of myth and legend. His long shadow is well-deserved.

Cover illustration: Interpretation of Sigurd made by Jenny Nyström. Wikipedia.

Text: Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.