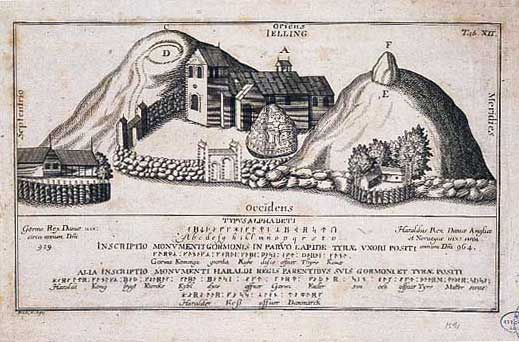

And so, today we conclude rune month with two of the most magnificent rune stones of the Viking Age. The world-famous Jelling stones of were erected in the mid-10th c. AD at site of Jelling, central Denmark, then the seat of power for the kings and queens of the royal dynasty known as the House of Gorm.

This dynasty takes its name from King Gorm the Old, the earliest historically-verified king of his lineage. Gorm’s father is referred to in later, semi-legendary sources as Harthacnut or Cnut I, himself said to be the son of the legendary Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye—this would make Gorm the grandson of Sigurd and, by extension, great-grandson of none other than Ragnar Lodbrok. Of course, kings have always been keen to tie themselves to illustrious figures, whether real or mythological. Though Gorm’s ancestry may be somewhat shrouded in myth, his legacy was not, for his son and partner in many of his achievements was the much more famous Harald Gormsson, later known as Harald Bluetooth.

King Gorm was a staunch pagan and—if you believe it from old chroniclers—a persecutor of Christians. He and his son Harald were said to be militantly opposed to the advance of the religion into Denmark, bringing them into conflict with their neighbours to the south. In this he may have been aided not only by his son but by his wife, Queen Thyra, a formidable and revered woman who is said not only to have contributed to building the Danevirke—the great southern fortification across the Danish peninsula—but to have personally led troops in battle against the Germans. Whatever the truth of these stories, Gorm’s devotion to his wife appears to have been strong, as after her death he raised the first of the Jelling stones in her honour in 950 AD. This stone is simple, devoid of adornment, but features large, clear runes on two sides reading (Old Norse then English, translation by the National Museum of Denmark):

“Gormr konungr gerði kumbl þessi ept Þyri konu sína, Denmarkar bót.”

“King Gorm made these runes in honour of his wife Thyra, the pride of Denmark.”

Around the time of Gorm’s death, an enormous burial mound was commissioned at Jelling, on top of a pre-existing mound dating to c. 500 BC. This mound contained a double burial chamber, and so it is presumed that the monument was raised by Harald in order to lay both his parents to rest in dramatic pagan fashion. He may also have underlined this with another monument at the site: the largest stone ship setting ever found in Scandinavia, with the mound at its centre.

But by the time archaeologists investigated the mounds, the chamber was empty. Neither Gorm, nor Thyra, nor anyone else, remained. Why might this have been so?

King Harald had begun his reign as a strong pagan like his parents. However, in the early 960s AD—only a couple of years at most after he had built his great monument—he made the extraordinary decision to accept baptism, becoming the first Christian king of Denmark. He ordered a new construction alongside his older monuments, a wooden church. Thereafter, he commanded that his subjects also become Christian, and even posthumously converted his parents. Having them lie in a pagan burial would not do, and so he had their bodies exhumed from the barrow and reburied in his new churchyard.

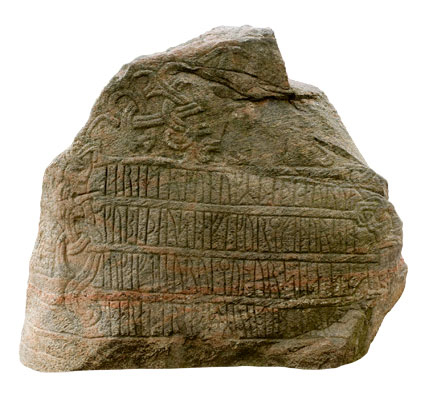

He thankfully chose not to tear down his heathen monuments (perhaps he could not quite bear to see all his hard work go to waste, or just enjoyed how impressive they looked on the horizon). In fact, he added a second enormous mound to the site, which overlay one of the two ends of the stone ship. But he also added what we might think of as a sort of “asterisk” between these mounds: the second of the Jelling stones. This stone is three-sided, with the vast majority of the inscription contained on one side and carrying over in a single line on the two others. It reads (Old Norse then English, translation by the National Museum of Denmark):

“Haraldr konungr bað gǫrva kumbl þausi aft Gorm faður sinn auk aft Þórví móður sína. Sá Haraldr es sér vann Danmǫrk alla auk Norveg auk dani gærði kristna.”

“King Harald ordered these kumbls made in memory of Gorm, his father, and in memory of Thyra, his mother; that Harald who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.”

This inscription not only reaffirms Harald’s reverence for his parents, but also boasts of two achievements: the conquest of Norway and the Christianisation of the Danes. The first of these is somewhat contested, it being uncertain exactly how much of Norway he really held influence over. As for the second, we certainly cannot doubt that Harald received baptism—but we must consider that converting an entire kingdom is hardly an overnight process and it is possible that many Danes went on being quietly pagan for generations after their “official” conversion. Harald, however, seems to have taken his new faith seriously—seriously enough to go through the ordeal of exhuming his parents’ bodies in order to rebury them according to it.

But the second piece of evidence for Harald’s commitment to Christianity is on the second side of his runestone, which features a bound man clad in a flowing garment, arms outstretched, a halo around his head. It is almost unanimously agreed that this is the earliest pictorial representation of Jesus Christ known from Denmark. Keeping with the theme of the imagery, it is on this side, also, that Harald claims to have made the Danes Christian. In other ways, the stone was more of a classic, featuring flowing double-ribbon designs in a fashion very typical of its day.

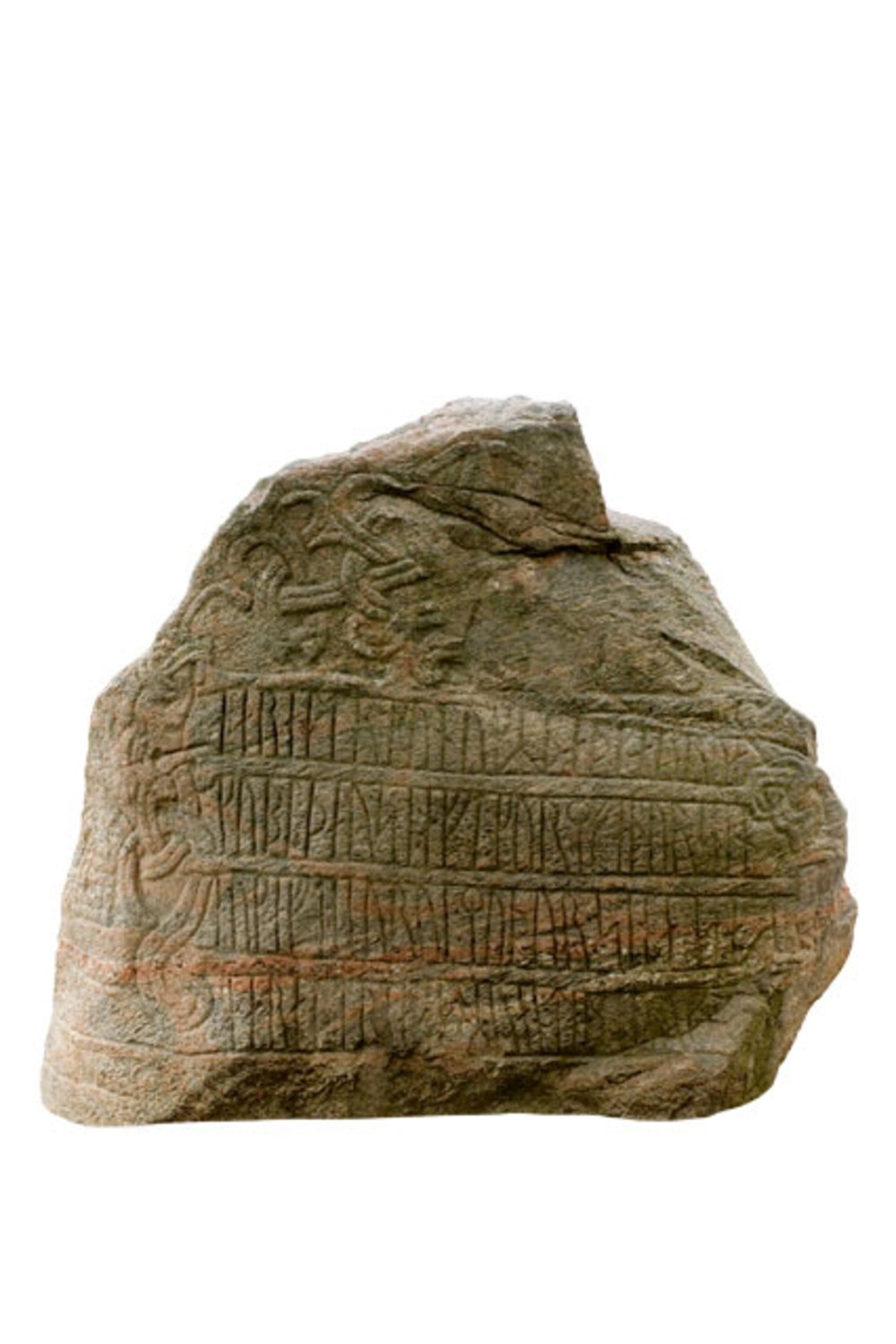

You might be familiar with the fourth of the Viking art styles, called the Jelling style, popular from c. 900-975 AD—and you might, then, be surprised to learn that the Jelling stone itself is not made in this style! In fact, the Jelling stone is decorated in the Mammen style, itself in vogue from c. 950-1025 AD. This is most clearly seen on the final panel (actually the second), which is a little more in line with other runestones we have explored thus far this month. This side features at least two animals: a quadrupedal mammal with both horse- and dog-like elements and strange, hook-like feet, often referred to simply as the “Great Beast” motif; the other a serpent, coiling around the Great Beast in multiple loops. These creatures are usually interpreted as being locked in a struggle, but the exact symbolism of this image (if any) is not universally agree-upon. It is, however, on this side that Harald stakes his claim to Norway, and so the scene of the animals’ battle may stand represent his conquest of the north.

Harald’s stone was originally painted, and archaeologists have been able to reconstruct the colour scheme based on the few fragments of paint that remain in the engravings. A full-sized replica of the stone, adorned with the original colour, stands today in the National Museum of Denmark as the centrepiece of their runestones exhibition. The originals, as is fitting, remain in place by the mounds of Jelling, protected from the elements with a high-tech glass casing that controls the interior climate and prevents any further deterioration. Clearly, there is no better place to see such monuments than in the place they were originally built, and meant to be seen.

The runestone of Harald Bluetooth is one of the most spectacular examples of Viking Age art, as well as a crucial record of historical events (not least, the foundation of the modern state of Denmark, leading to its nickname, “Denmark’s birth certificate”) and a touching memorial to family ties. It has been used as a piece of political and religious propaganda for over a thousand years, and captivated rune enthusiasts in a way few other pieces can. It represents a fitting end to our monthlong adventure through the world of the runes, and we hope you have enjoyed it as much as we have.

Text: Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover Photo: National Museum of Denmark.

About the author

Archaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts from Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, Canada) and a Master of Arts from Uppsala University (Uppsala, Sweden). My specialisation lies in bioarchaeology broadly, with a primary focus on mammalian zooarchaeology, and a special interest in the Late Iron Age of Scandinavia (though you can occasionally catch me sniffing around Egypt as well).

In my Master research I conducted an osteological analysis of domestic dog remains from Valsgärde cemetery, Sweden. The aims were to identify the number of dogs buried at the site, reconstruct the appearance of the dogs, and identify any patterns and changes between the Vendel Period and Viking Age.

I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between humans and animals, domestic and wild, in societies throughout the world. Through archaeology, I hope to shed light on this crucial part of our shared heritage.