What happened to money if a European country went broke in the 17th century? And how did a bizarre coin lead to the introduction of paper bills, as well as central banking systems?

Well, given paper money did not exist in Europe in the beginning of the 17th century, coins were the way to go. At the dawn of coinage use, coins were made from precious metals and their worth would be equal to that of the weight of metal they were made from (a standardised measure). The problem, though, is that if such a state is bankrupt, then it has already run through its supply of precious metals (or, if the state had its own mines, they had begun to dry up). This left the reigning government with only metals of lower worth.

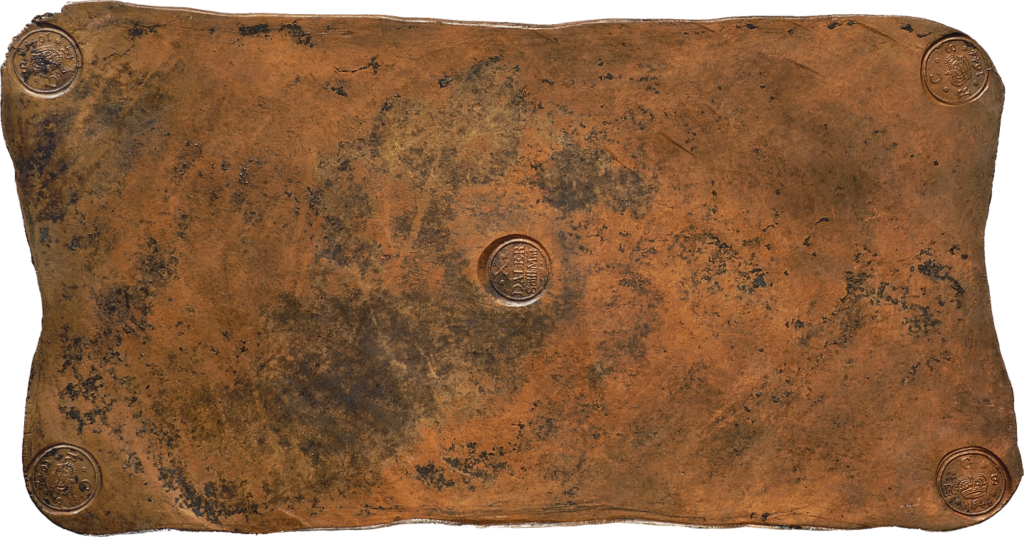

And this was the case in Sweden during the 30 Years’ War (1618-1648). Instead of making the “daler” (the coinage used during this time) in silver as per usual, the Swedish crown began to make it from copper as the copper production, in contradiction to the silver production, was quite high. However, for a copper coin to have the same worth as a silver daler in terms of weight, more copper was required, resulting in a somewhat bizarrely-sized coin.

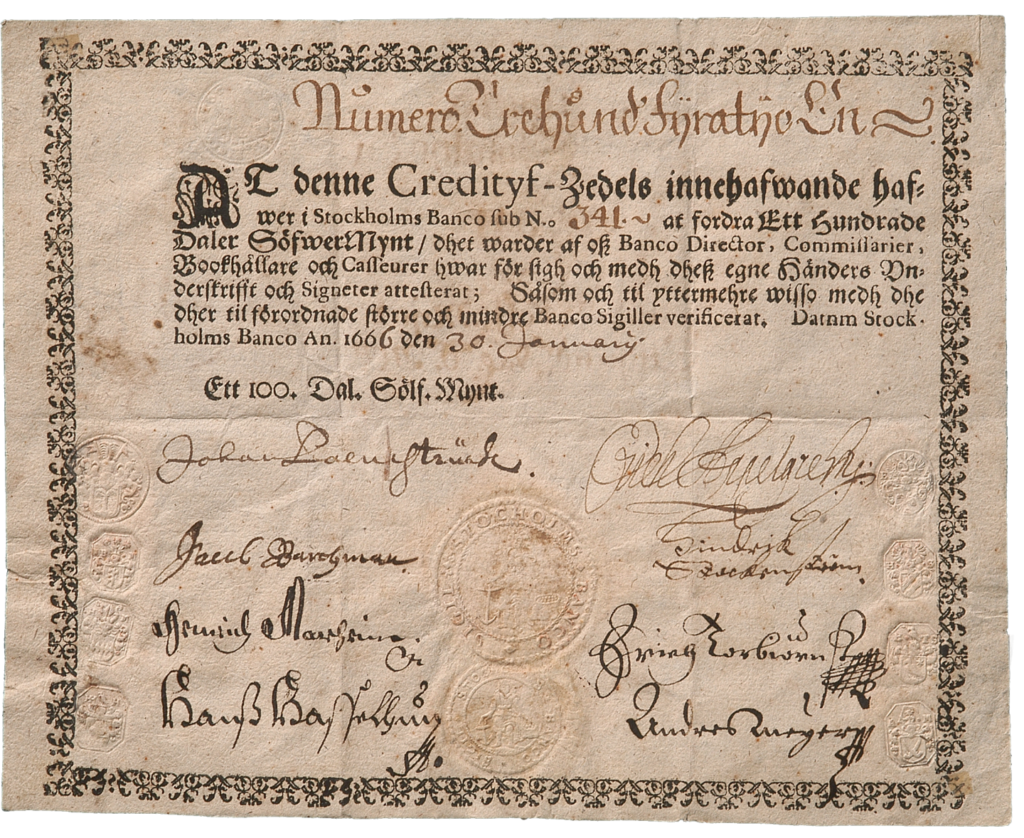

These coins were worth 8 daler but were quite impractical, as they could weigh as much as 15 kilograms—not so very convenient to carry around. The invention of this coin led to three things: erosion of the monetary value of weighted previous metal, Europe’s first paper bills, and the formation of the world’s oldest central bank.

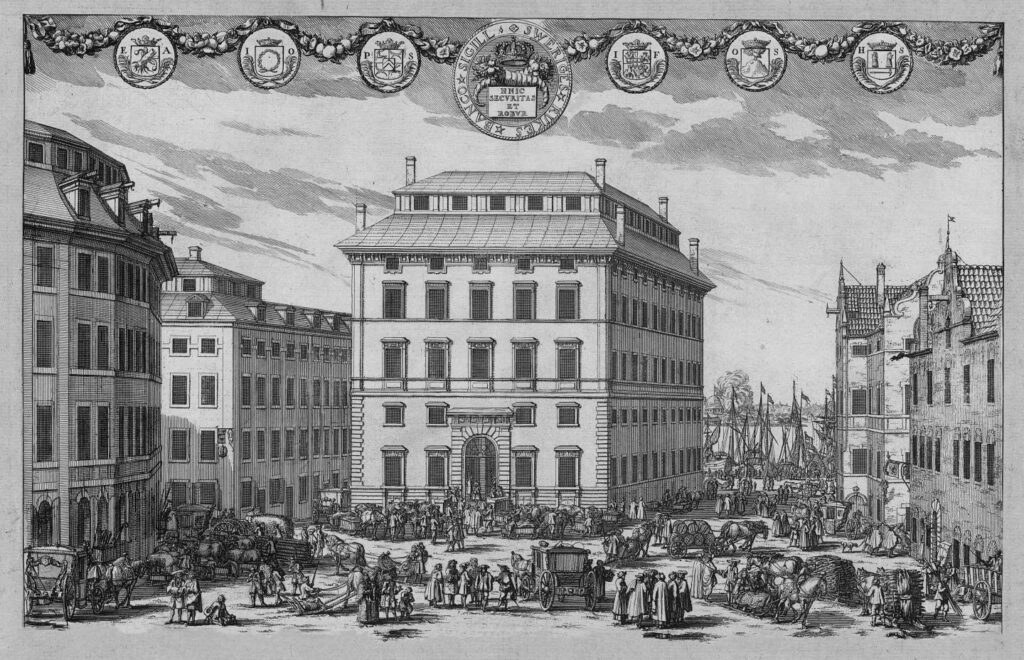

The erosion was due to the increased production of silver daler as soon as silver were available again as the copper versions were impractical. The impracticality of the coin led to the usage of Europe’s fist paper bills, which came into use in 1661 in Stockholm, Sweden. And the usage of paper bills in its turn led to the need of a central banking system to verify their monetary value, and thus Riksbanken (the National Bank) was founded in 1668. The copper coin—a solution for the lack of silver in scarce times—thus led to new innovations which have led to the modern currency system as we know it, as well as the western banking system. This humble but bizarre coin is therefore a crucial part of global history and development.

But what happened to the enormous coins? They were in use for quite some time before being abolished in 1777. However, there were not many of them left by that point—since they were not only to be used as currency but could also legally be hacked up and melted for the copper itself, many of them ended up suffering this fate in a strange callback to the “hack silver” phenomenon of the Viking Age. Therefore, few survive to this day.

But if you have one, you are in luck, because the return on the coins prove they would have been quite a good investment for those with a little patience. In 2020, a coin from 1659 was sold at the auction house Bukowski’s for a whopping 2.45 million crowns, or approximately 234,000 euros.

The coins are today mainly found in museums and private collections.

Cover Photo and text: Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2022 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Iron age Scandinavian archaeologist with a bachelor in Liberal arts with major in Archaeology and a bachelor in Art history with major in Nordic art, both from Uppsala University, Sweden. Exchange studies at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, and University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Master of Arts (two years) in Archaeology with specialization in burials, ship burials, and artefact management and interpretation, also from Uppsala university, Sweden.

In my master thesis I created an analyzing method to handle large quantities of artefacts, a method descended in Art History. I also created a method with elements of theory to perform a spatial analysis on graves. This also derived from Art History. The methods were applied to ship burials at Valsgärde, Upland, Sweden.

As Editor-in-chief, I am responsible for the publication and over all work with Scandinavian Archaeology, a job I deeply enjoy. I also founded the magazine in late September 2020.