It was the late 19th century, and the age of National Romanticism was in full swing. Scandinavians were diving into the Sagas of the Icelanders for tales of their ancestors’ exploits. One episode held an exceptional fascination, the tale of Leif “the Lucky” Eiriksson and his voyage to Helluland, Markland, and, most famously, Vinland—mysterious lands on the east coast of what was now called America. The idea of Vikings being the first Europeans to set foot in the Americas was a fascinating one, but so far, there was no archaeological evidence for it. Remember, this was well before the sensational discovery of the Norse settlement in L’Anse aux Meadowes, Newfoundland.

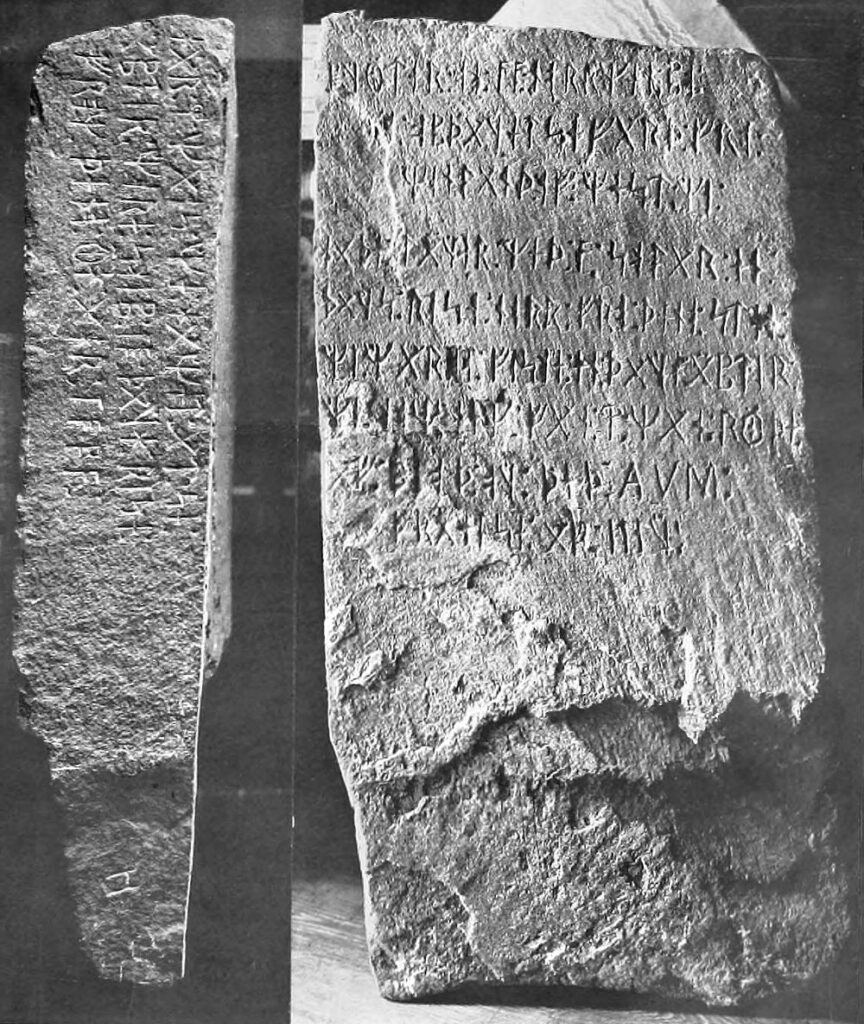

Enter Olof Öhman, a member of the Swedish immigrant community in Minnesota. In 1898, he presented a large slab of sandstone, which he claimed to have dug up in a field near the town of Kensington, covered with Norse runes.

The runes told the story of eight götar (Götalanders) and twenty-two norrmen (Norwegians) who made the journey inland from Vinland in 1362. Some of these intrepid explorers were fated never to return—after most of the crew had spent the day out fishing, they returned to find ten of their compatriots “red of blood and dead”. Slain by foes unknown! “AVM” (Ave Virgo Maria) is carved in Latin letters to deliver their souls from evil.

Here it was, at last: real archaeological proof. The Vikings had been to America, and gone even further than even the saga writers had dreamed!

But…could it be trusted? It took until 1910 before the stone could actually be examined by archaeologists and linguists, and almost immediately, suspicions arose.

For one thing, the runes were remarkably clear-cut and sharp. Typically, runestones after centuries are heavily weathered and can be notoriously difficult to decipher. Certainly there were sections of this inscription missing, but the runes that did survive did not exhibit any sign of erosion whatsoever. This was not necessarily a death-knell for the Kensington Runestone, as preservation is a tricky thing, and perhaps the stone had been protected from the wind and rain that otherwise would have smoothed and blurred the text. Still, it was unusual.

Additionally, compared to the majority of runestones, the text is presented in far straighter, widely spaced staves without the carved lines typically used to delineate them, and the “font” in which the runes are written looked distinctly different—neater, more precise. In addition, this would be the only runestone to use Arabic numerals, in the form of a date (1362). Again, however, this could (with some charity) be explained. By this point in history, the church had become a far greater influence on the literacy of Scandinavian society, and it is possible that the man who carved the runes might have been familiar with the ways in which clerical texts were written, and sought to emulate that in stone form.

More damning was the evidence from linguistics. Experts in the Nordic languages who examined the stone were able to ascertain very quickly that the language in which the stone was carved did not closely resemble any medieval Norse dialect. It was given away chiefly by several anachronistic phrases and words which did not enter the Nordic languages until the 16th century, as well as the lack of certain grammatical cases which would have been present in Early Old Swedish (the language of the 14th century). More generally, the text was so similar to modern Swedish that it was far more easily intelligible to a 20th century Swedish speaker than any medieval dialect.

Nevertheless, over the course of the century since its discovery, periodic attempts have been made to argue for the stone’s authenticity. But on the vast whole, the evidence—and thus, scholarly consensus—points to the Kensington Runestone being a fraud. It remains unclear who carved it. Olof Öhman is the only viable suspect we know of, but any number of the Scandinavians settling in the region in the 19th century with a basic knowledge of runes might have done so as well (that the stone just so happened to be found by Scandinavian immigrants newly arrived in the country, as opposed to any of the many peoples who had lived there for centuries prior was also considered…convenient).

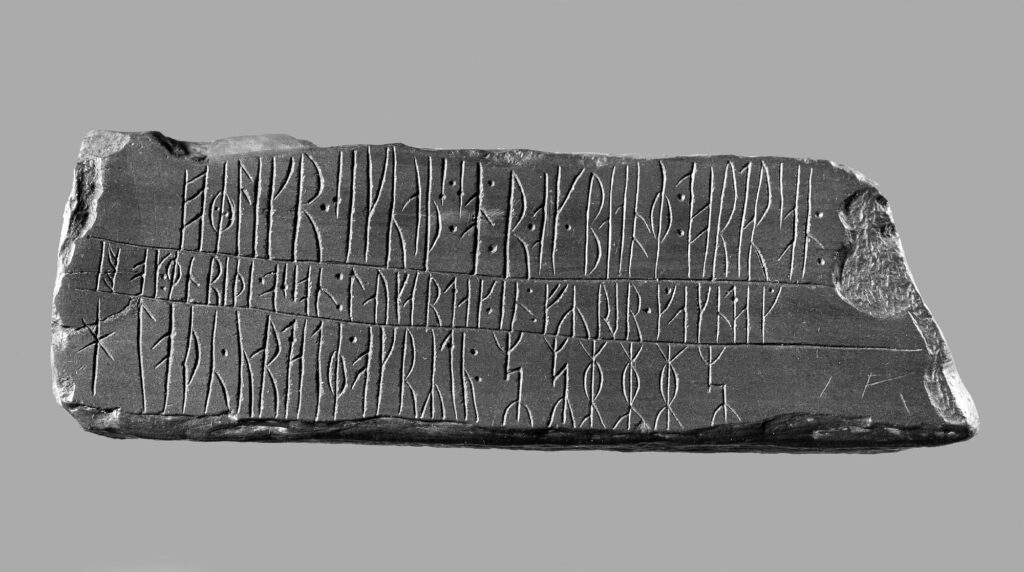

This means, then, that the Kingittorsuaq Runestone, found in Greenland in 1824, remains the only genuine Norse runestone as of yet discovered in North America. This stone, dating to the early 14th century and thus only a few decades before the purported date of the Kensington Runestone, is an excellent point of comparison. While its inscription is short, it far more closely resembles the “classic” style of runic carvings, casting further aspersions on the unusual font and arrangement of the Kensington Runestone.

That the Vikings reached North America is undisputed. That they and their medieval descendants explored further inland in North America is not impossible. Some might even consider it plausible. But we still await hard proof—proof which the Kensington Runestone does not provide.

Text: Christopher Nichols. Copyright 2023 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover image: Leiv Eirikson discovering America. Christian Krohg (1893).

About the author

Archaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts from Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, Canada) and a Master of Arts from Uppsala University (Uppsala, Sweden). My specialisation lies in bioarchaeology broadly, with a primary focus on mammalian zooarchaeology, and a special interest in the Late Iron Age of Scandinavia (though you can occasionally catch me sniffing around Egypt as well).

In my Master research I conducted an osteological analysis of domestic dog remains from Valsgärde cemetery, Sweden. The aims were to identify the number of dogs buried at the site, reconstruct the appearance of the dogs, and identify any patterns and changes between the Vendel Period and Viking Age.

I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between humans and animals, domestic and wild, in societies throughout the world. Through archaeology, I hope to shed light on this crucial part of our shared heritage.