Horned helmets. Traditionally, the Vikings are associated with their incredible, fashionable headgear, right? The beautifully formed bull’s horns, attached to each side of the helmet in perfect symmetry, creating a terrifying and lasting impression, making enemies turn and run since 793 A.D. Normally carried by the Viking warrior into battle, raids, and… wait, what? In case it is not obvious to you already: all of this is nonsense and is one of the most widespread myths concerning Scandinavian pre-historic culture. Today this version of the Viking is, thankfully, debunked but once upon a time he was very much alive. Where did this manly-man Viking with the horned helmet come from? One thing is for certain: not history, and he was certainly not created from material culture. It was within the sphere of popular culture that he was born, this iconic horned Viking. And oh boy, was he popular!

A Piece of Art

In 19th Century Europe, there was an upswing in popularity and interest in Norse mythology. Naturally, Scandinavian history also witnessed a revival. Interest was especially focused within the sphere of popular culture and art where heroes, kings, and gods were commonly depicted and portrayed. Where the artists got their inspiration differs between textual sources such as the sagas and collected materials such as swords, shields, axes, etc. presumed to be from the Viking Age. One important question remains: where did these artists find the inspiration for horned helmets? The sweet and short answer to this is that we simply have no idea. Somehow the horned helmet trend in connection to Vikings and Norse mythology truly exploded, with not just one or two artists portraying the feature but several artists adopting it. Clearly, this was a trendy and apparently fresh way of portraying these seafaring heroes, if one can judge from 19th Century paintings alone. Let us go through at least some of the early birds of the “very modern but not so accurate Viking Age helmet”.

The Ring of The Nibelung (more commonly known as The Ring) is a 19th Century opera by Richard Wagner. It is based on The Nibelung Song (Nibelungenlied), a German medieval manuscript from the 11th Century, as well as Norse mythology such as the Volsung Saga and the Poetic Edda. Naturally, we get to meet one or two Vikings amongst the heroes and gods in Wagner’s four-act opera. And yes, according to the illustrations inspired by The Ring, some of them did in fact sport horned helmets. Two names worth mentioning here are Michael Echter and Carl Emil Doepler, both German painters working in close contact with Wagner. Michael Echter was commissioned by King Ludwig II to decorate his palace with murals inspired by The Ring, of which the king had grown very fond. Sadly, Echters frescos were destroyed together with the palace during WWII and are therefore lost forever. Luckily, Franz Hegel repainted some of Echters works. In one of the repainted illustrations, we can see a tall, rather big, Viking warrior wearing the now very famous horned helmet. This is also one of the earliest examples of the horned helmets in connection to Norse mythology and Vikings.

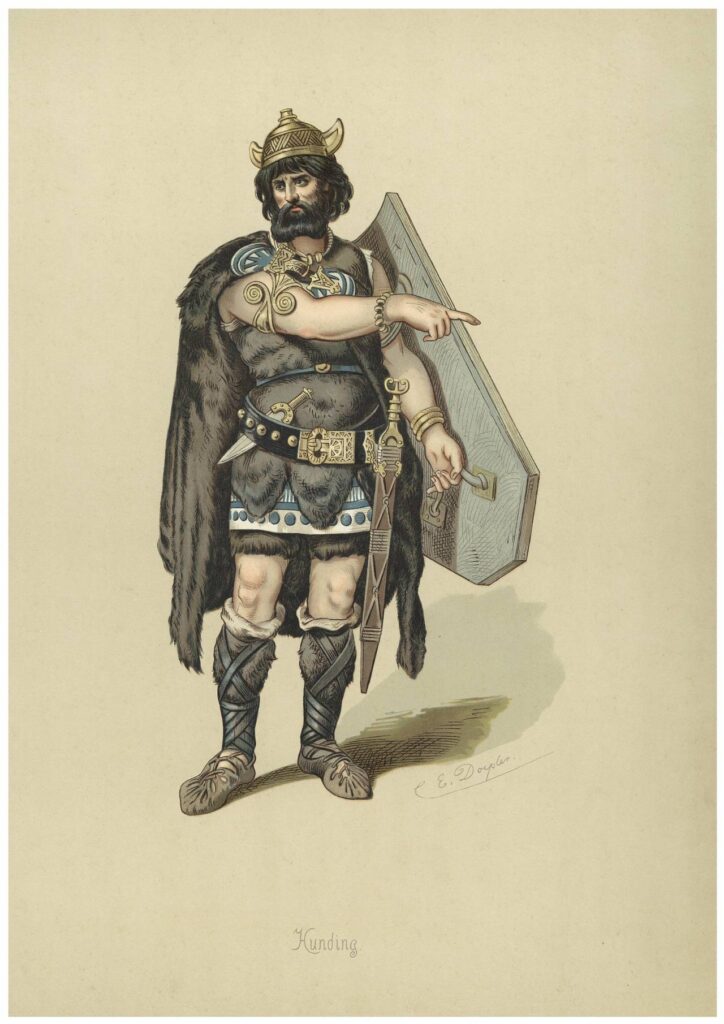

Soon after, Carl Emil Doepler would follow Echter’s example and make the Viking even more fashionable. Doepler was commissioned by Wagner himself to create appropriate costumes for the premiere of The Ring in 1876. One of the characters who was honoured with adorning said horns was Hunding, a man who in Wagners play is a warrior of giants’ blood. Interestingly enough, Doepler had studied Viking Age (or presumed to be at the time) artifacts by visiting several museums. The weaponry depicted is most likely inspired by actual archaeological 19th Century findings. Hunding’s vestment and helmet, on the other hand, are a result of artistic freedom.

Another interesting interpretation made by Doepler in connection to The Ring is the one of Odin. While this might be considered a sidestep from this article’s subject it is worth mentioning. While Doepler spared Odin from being given horns, he instead gave him wings. Yes, wings. When things could not get more confusing, they just did… These are commonly used in popular culture when illustrating the Norse Valkyries. Doepler most likely saw it fit to give Odin wings resembling that of the Valkyrie’s, in his role as their leader. The Norse Valkyrie were the ones gathering the dead to bring them to Odin and Valhalla, or Freyas Folkvang according to mythology. These wings would soon become synonymous with Odin, and until this day they are commonly used in illustrations and movies. This is perhaps artistic licensing at its best, people!

Making It Into History

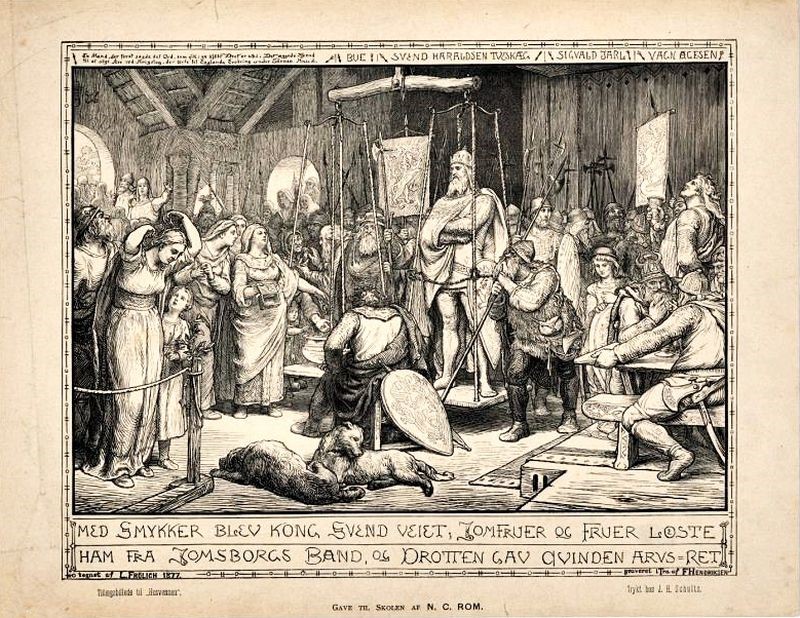

Lorens Frølich, a Danish artist famous for portraying scenes from Norse mythology, is also one of the originators of the horned Viking helmet. He more or less spent his whole life portraying the Norse and created his own, very distinct, art style along the way. When you see a Frølich, you know it is a Frølich. His art piece of Sweyn Forkbeard, king of Denmark and Norway 985-992 A.D. and 993-1014 A.D., captured by the enemy (Jomsvikingarna) was made in 1877. Here Sweyn is surrounded by women, children, dogs, and… yes, a “Viking” with his horned helmet, presumably drinking a mug of mead at the far-right table because why not? He could be listening to the discussion on whether Sweyn should be set free, and to what cost. This is the first known illustration of the horned Viking recorded in course literature, for which the piece was specifically made. This is what makes it interesting, and special. Up until Frølich’s interpretation of Sweyn Forkbeard’s capture, the horned helmet appears in paintings inspired by Norse mythology rather than historical happenings. This illustration gives the horned helmet a factual rather than fictional context and strengthens the phenomena further.

The Viking of Today’s Popular Culture

This phenomenon did not stay in the 19th Century but would stick around for a while longer within popular culture and especially art. Today the myth surrounding the Viking helmet is considered debunked. However, this does not stop people from continually depicting Vikings with horns. Some ironically, some artistically, some may even be the result of a strong belief that the horns were a part of the original vestment. If you have ever watched a game of football or ice hockey featuring Sweden, it is hard to not notice the men and women dressed in their blue and yellow of the Swedish flag, topped off with a mandatory helmet (that can be purchased at most tourist souvenir shops in Stockholm’s Gamla Stan). Some even take it even further and also feature blonde braids. Another example of the Very Famous Viking Helmet is also witnessed in the emblem of the Minnesota Vikings American Football team, whose mascot Viktor the Viking also adopts the fashionable horned helmet, accompanied with blonde braids.

So, What Did They Wear?

While we could keep rambling on and on about the horned helmet, we might have to clear some things up instead. What kind of helmet did the Vikings actually wear into battle? This is the one-million-dollar question, for sure, because we simply do not have enough facts concerning their actual headgear. Why? Simply because helmets are not found in contexts dating to the Viking Age. Currently, only one Viking Age helmet has been discovered, dating to c.875 A.D. and found in Gjermundbu, Norway, in an exceptionally rich male grave dated to the 10th Century. Since then, no more helmets stemming from this period have been gathered to contribute to our Viking Age collections. And no, in case you were wondering, the Gjermundbu helmet does not show any signs of ever being decorated with horns. Several helmets, dating from the Vendel Period (550-793 A.D.) (which precedes the Viking Age) have been recovered from graves. Guess what? No horns on them either.

Why do helmets disappear from the grave materials in the Viking Age? This we do not know. One of the reasons could be that the helmet simply became less personal during the Viking Age than previously, and thus was not seen fit to be included in burials. Weapons of all sorts such as swords, shields, spears, etc. are found in Viking Age graves which could be interpreted as them possessing a higher personal value. Weapons were likely of greater use anyway when reaching Valhalla in order to engage with the Giants every night, alongside Odin, rather than possessing a helmet for head protection. Judging from this video the Danish Vikings might have considered it a little bit embarrassing wearing a helmet into battle, could this be the excuse the real Vikings would use too? The Viking Age helmet will remain a mystery for now. As much as the horned helmets will remain a debunked popular culture phenomenon stemming from artistic licensing rather than facts. Artistic freedom should always be encouraged and after all, it made life for Scandinavian sports fans a lot easier in deciding what to wear to games of all sorts. For this, we thank thee.

Cover photo: Henrik Rosenborg. Copyright 2021 Henrik Rosenborg Art.

Text: Elfrida Östlund. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

About the author

Medieval Scandinavian Osteoarchaeologist with a Bachelor of Arts in Archaeology specialized in Osteology, from Uppsala university, Campus Gotland. My Bachelor's thesis focused upon the correlation between social status and health in the medieval church ruin S:t Hans in Visby, Gotland.

Master of Arts in Archaeology (two years), Uppsala university, Campus Gotland. In my Master's thesis I analyzed human remains (isotope-, bone density-, and morphological analysis) from individuals found at the Cistercian Roma monastery, Gotland. My aim was to get an understanding of the relationship between the living and the dead by studying both human remains and burial constructions in an isolated community context.

My future goal is to work full time as an archaeologist and also finish a PhD focusing at late Iron Age and early Medieval studies in Osteoarchaeology.