“You must find the runes and read them. Strong symbols, powerful symbols stained by the mighty sage, hewn by the potent Powers, all etched by the runemaster.”

– Hávamál, the High One’s Sayings (trans. Jeramy Dodds)

Runes are the written language used in Scandinavia during the Late Iron Age. The runes are highly associated with the Vikings—but in fact, they were used long before the Viking Age, and persisted in their use in certain parts of Scandinavia as late as the 18th century. The Latin alphabet now used in the western world lived side by side with the runic inscriptions longer than most of us are aware of. Nowadays, only trained experts and a handful of enthusiasts can understand them, but in their heyday, it is probably that most people in the Scandinavian world could read runes.

As a standard system of writing, runes were used for a wide variety of purposes and in a wide variety of different media—everything from memorials to graffiti, carved on everything from stone to wood. But in addition to their mundane function as an alphabet, runes also have a mythological component, being heavily associated with magic and divination, the domains of Odin himself.

In this article, we will give you a crash course into the weird and wonderful, dark and mysterious, sometimes even funny or romantic, but always interesting, world of runes.

So, what are runes, more exactly?

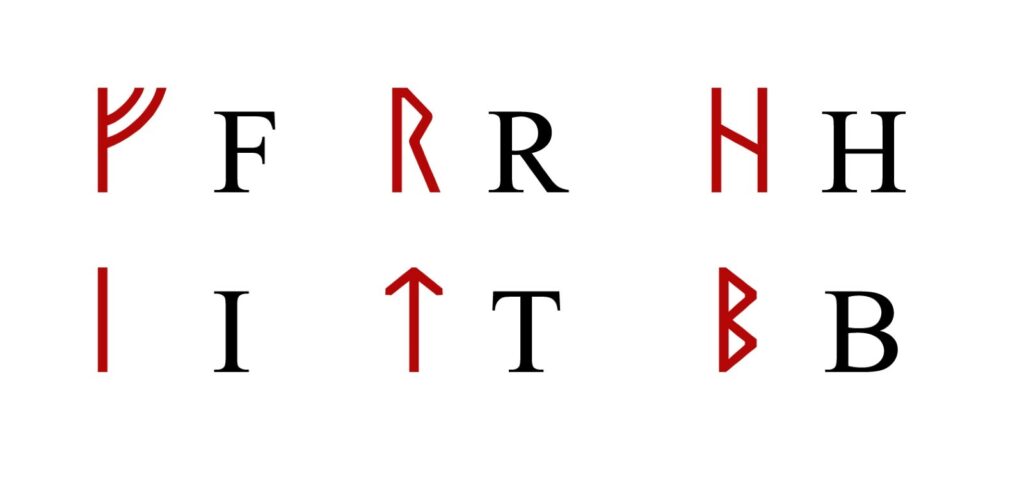

Runes are the letters of the Old Norse alphabet—or, more accurately, alphabets, as there are several different versions depending on time period and place. The most common rune alphabets are called the Elder Futhark and the Younger Futhark, the word “futhark” being a transliteration of the first six runes in both versions of the alphabet, ᚠᚢᚦᚮᚱᚴ (F; U; þ, pronounced like English ‘th’; A; R; K). The Elder Futhark consisted of 24 letters, and was used from the mid-2nd century AD to around 750 AD. After this, the Younger Futhark—with only 16 letters—developed in Scandinavia, and was used throughout the Viking Age to the Middle Ages.

Runes likely originated in northern continental Europe, and were used by a wide variety of Germanic peoples in the Migration Period. It is theorized that the futhark was inspired by both the Latin and Greek alphabets, as it was during this time that Germanic peoples of northern Europe were coming into sustained contact with the Roman Empire. One of the theories is that Norse traders who traveled down in the continents were inspired by the traders there who could communicate with each other through writing. When they came back to their homelands, they developed their own written language loosely based on the alphabet used further south.

The first known appearance of runes in Scandinavia is on a comb dating to the 2nd century AD, found at the site of Vimosen, Denmark. It was found in a bog alongside some 2500 other objects, all deposited as offerings over a period of roughly 300 years. The comb was inscribed with runes reading “Harja”, which has been taken to be the name of the owner. In these early days, runes were often used like this—to spell out the name of the maker or the owner of an object—but came to be used in more complex contexts later on.

However, there were no runes representing numbers in the futhark. The numerals that we use today in the western world are derived from Arabic numerals, not Latin. If one would write a number in a Norse runic inscription, one would have to spell it out. Because of this, runic inscriptions featuring numbers are rather uncommon.

Rune stones, rune sticks, or rune bones?

The most famous items for rune carvings are the huge rune stones that dot the Scandinavian landscape, thanks in great part to stone’s durability and resistance to degradation making them the most likely features to survive through time. However, runes were commonly also carved on wood or bone, and in fact, the majority of rune carvings were likely made in wood: it is a soft and easily accessible material that can be carved with common tools, unlike stone. The shape of the runes, with vertical and diagonal staves and branches, also flows well with the grain of wood, and it is therefore believed they were specifically developed to be able to be carved with ease into wood. The downside of this is that wood is an organic material and therefore decomposes much more easily, and so the majority of rune sticks have long since rotted away. However, they can occasionally be preserved if they are buried in oxygen-proof conditions, such as deep inside acidic bogs. Runes can also be carved on bones, horns, and metal, which tend to preserve much more reliably than wood.

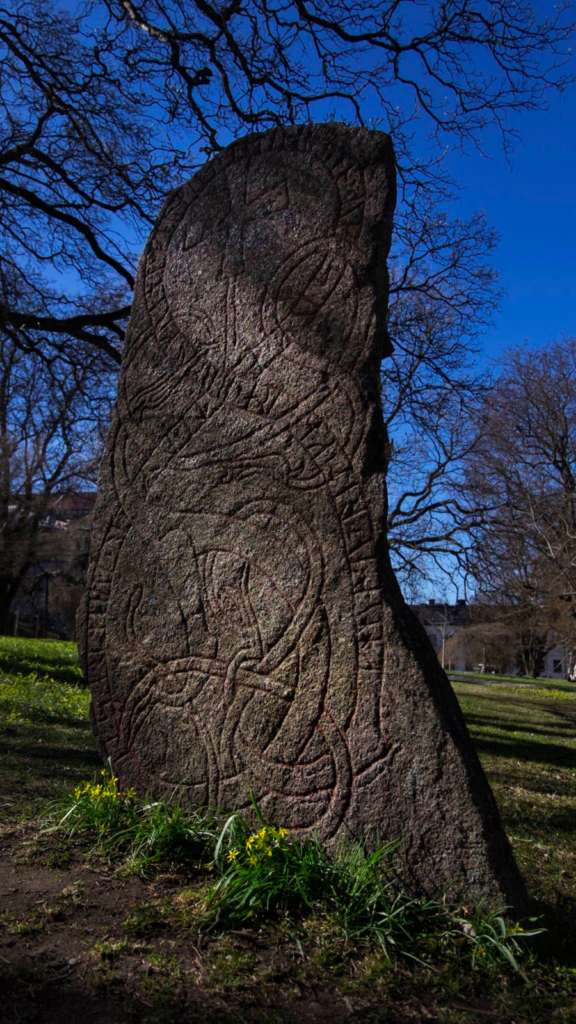

Rune stones

The earliest-known rune stones can be found in Norway, all dating to the mid-4th century AD: the Tunestone, the Hogganvikstone, and the Einangstone. But even though it appears that rune stones first appeared in Norway, they are more commonly found in Sweden and Denmark. While Norway is home to 137 rune stones, Denmark (including certain parts of Sweden that were “Danish” during the Viking Age) has 273 stones; Sweden leads by far, however, with a full 2881. The area with the highest density of rune stones is the Mälar Valley of central Sweden, and more specifically in the region of Uppland, featuring 1334—nearly half of all Sweden’s rune stones. Only a handful have been found outside Scandinavia itself. The British Isles are home to approximately 60, including one in what is now the Republic of Ireland. Iceland, however, lays claim to only 17 rune stones.

Rune stone production reached its peak during the years 900-1100 AD, after which they ceased to be produced altogether. It is believed that the end of rune stone production is related to the conversion to Christianity, as in most areas rune stones stop being made soon after the establishment of a local bishopric. But a number of late stones feature Christian text and crosses, which may suggest that the process of conversion was gradual, with old traditions absorbing new religious elements before being replaced by them altogether. One such is the Jelling Stone in Denmark, featuring the earliest pictorial representation of Jesus Christ in Scandinavia. This was erected to commemorate the baptism, around the year 930 AD, of the Danish king Harald Bluetooth, who had begun life as a devout pagan but became the first Danish king to convert to Christianity. In Sweden, where many rune stones were produced containing Christian elements alongside so-called pagan elements, one hypothesis is that local people had begun to practice their own, localized version of Christianity before the church had an official presence in the region. Once a full-time local clergy was established, however, official Christian laws might have been administered to put an end to older practices considered non-Christian, and the carving of rune stones may have fallen into this category.

The Swedish island of Gotland, as usual, provides an interesting counterpoint. Rune stones were raised but were not widespread on Gotland, as the long-standing local tradition was instead the carving of picture stones. But runes themselves were still known here, and were inscribed on gravestones up until the 15th century, long after the disappearance of rune stones on the mainland. Additionally, lines of runes containing Christian messages can be found carved into the walls of medieval Gotlandic churches. This is an interesting example of the ways in which islands have always developed unique identities within the broader cultural context they inhabit.

Who used the runes and who could read them?

During the Viking Age, it is believed that most people (at least the free ones) could read and possibly even write. This is believed for a handful of reasons. One of them is the rune sticks that have been found containing more everyday text and subjects. Runic graffiti have also been found, such as the Maes Howe cave in Scotland, which features several of the most banal and crude runic inscriptions you are likely to ever read, certainly not the type of writing that professional scribes are likely to have spent much time on.

Another reason is the rune stones themselves: to carve a rune stone was something that required skill and expertise, and the ones who carved rune stones did so by profession. They would receive custom orders for rune stones, with a client dictating what the inscription should read, and then the stone maker would “sign” his work at the end of the inscription (for example: “Öpni made these runes”). The stones would then be painted and then placed in a well-visible position where they would be seen by many—and this is where the last argument weighs in. Why would one put a lot of money and effort into making a rune stone if most people could not even read it? Thus, the implicit assumption is that most people in Viking Age Scandinavia could indeed read runes.

What the language contained in the runes sounded like though, we do not know. There has been a lot of research on this topic and a lot of qualified guesses, but truth is, no one knows for sure what Old Norse sounded like. It is believed that more or less the same language was spoken over all the Viking world, divided into two broad dialects: East Old Norse in Denmark and Sweden, and West Old Norse in Norway and the North Atlantic colonies. Today, modern Icelandic is the closest living language to Old Norse in terms of grammar, and to a large degree the two languages are mutually intelligible, but they are believed to have slightly different pronunciations.

Runes after the rune stones

Runes remained in use in one form or another for a long time after the Christianization of Scandinavia. The rune sticks alluded to above remained in use for various purposes. While the Latin alphabet came to dominate in court and church documents, at least one medieval Scandinavian law code was put to parchment (vellum, more precisely) in runes; however, the use of runes in manuscripts seems to have been exceptionally rare. But even after the Latin alphabet had been fully adopted by the upper class, runes seem to have been commonly carved by people of a variety of social strata for their own purposes, and even came to be used to represent other languages, including Latin.

Also emerging in the Middle Ages, at least as early as the 13th century (though most date to the early modern period, in the 16th-17th centuries), was a peculiar type of artefact called a runic stave calendar, or “clog almanac”. Carved from wood or bone, stave calendars used lines of runes to represent the days of the week and the weeks of the year, marking out important dates and special occasions. They also correlated the cycles of the sun and moon on a 19-year basis.

In the modern era, another type of artefact strongly associated with runes are the small pieces of stone or bone that are carved with a single rune each, and cast on a surface to be interpreted by a fortune-teller (so-called “runecasting”). But despite this being one of the more popular forms of divination today, especially among those practicing Ásatrú or Heathenry, it could well be a largely modern innovation. No archaeological examples of such artefacts have ever been found, nor is it ever explicitly described in any Old Norse textual sources; only a handful of ancient and medieval texts make oblique reference to casting “chips” or “lots” carved with symbols for use in divination. Thus, even if the Old Norse did conduct a similar ritual, it is unknown how closely this might have resembled the modern version of it.

On a darker note, in the early 20th century, runes (in a modified form) were heavily incorporated into a new form of occultism, called Armanism by its creator, Guido von List. List believed that runes contained secret magic and teachings linked to Wotan (that is, Odin), and that they had been passed down through centuries by secret societies using a secret language. This bizarre theory might have been an innocuous one had it not been tied up in his explicit anti-Semitism, his views on the superiority of the “Aryan race”, and his dream of the establishment of a modern Pan-Germanic Empire. His theories laid the groundwork for numerous far-right occultist societies, most notoriously the Thule Society. Alongside the runes, List was also responsible for coopting the swastika as a racist symbol of Germanic nationalism; but while the runes have mostly recovered from this despicable misappropriation, the swastika has decidedly not.

Moving forward…

Thus ends our whirlwind crash course into the mysterious and checkered world of runes. If this piece has served to whet your appetite, you are in luck: over the next month we will be running a variety of pieces exploring runes in all their strange and wondrous forms in much greater detail (in addition to our usual, rune-less content as well). If there are any subjects you would like to see us cover, please let us know in the comments.

We hope you enjoy the upcoming month!

Text: Christopher Nichols, Lovisa Sénby Posse. Copyright 2021 Scandinavian Archaeology.

Cover Photo: Bengt A. Lundberg. Riksantikvarieämbetet.

Further reading: