One absolute favourite past time of archaeologists and historians is to play the “what if?” game. There are plenty of moments in the past, even seemingly small ones, which might have colossally changed the course of human history had things gone a bit differently. For example: what if the so-called “Visby lenses” had fallen into the hands of a curious early medieval scientist who jump-started the study of optics in Europe by half a millennium?

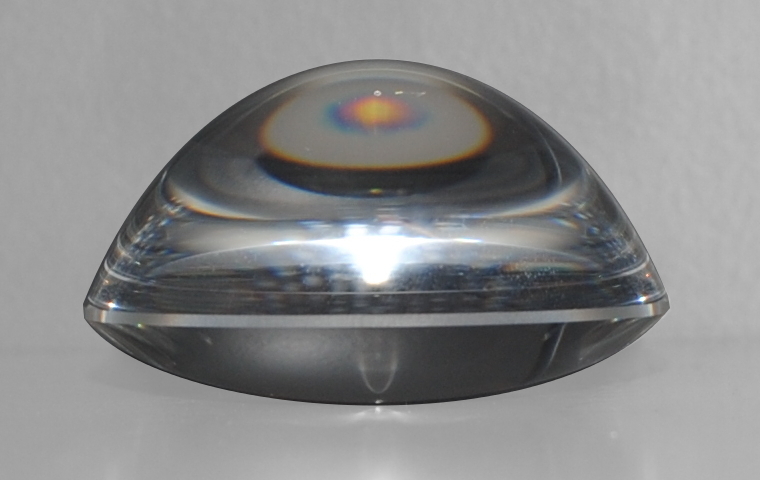

The Visby lenses are a collection of high-quality optical lenses found on the Swedish island of Gotland, in 1999. They are named after the city of Visby, the largest city in Gotland, though most of them come from the region of Fröjel. Dating from the 11-12th century, the quartz lenses are roughly dome-shaped and come in a variety of sizes, the largest measuring 50mm in diameter and 32.1mm deep at the centre. All the lenses show a “waviness” on the surfaces, which may have been due to repairs or bad polishing. Some lenses show evidence of having been reshaped slightly, possibly in order to mount the lenses in the silver filigree that makes them so distinctive. The collection at Fröjel also included pieces of rock crystal (the raw material for the lenses) as well as beads. Still more pieces of the collection are missing, and unfortunately appear to have been lost. The Visby lenses resemble the quartz “reading stones” invented by the Andalusian polymath Abbas ibn Firnas in the late first millennium AD, though their silver mounts are what make the Gotlandic examples really stand out. This has led to the speculation that the lenses themselves were manufactured in the Byzantine or Islamic world, then imported to Scandinavia and modified after the Norse fashion—or, possibly, that a Viking or Varangian had learned how to make them on their own travels to the east.

Lenses of this type have a variety of uses. Most prominently, they can be used as magnifying glasses to allow for reading fine text (hence the name “reading stones”), examination of small details in a variety of objects, or to allow a craftsman to create extremely fine detail in their work. By focussing light, they could also have been used to start fires, or to cauterise wounds and cuts to prevent infections. Given the silver filigree mounts, they may even have additionally been worn as decoration. Scandinavians of this time were known to have had “practical” jewellery; some examples include ornate brooches which doubled as boxes that women could keep things in; weighted arm rings in silver that could be hacked apart for currency; and ornate house keys that served as personal adornment, a marker of status, and also—well, a key to the house. The Visby lenses may have fit into the same category, as practical artefacts with an additional, decorative function.

Remarkably, when compared to modern optical lenses of the same style, the Visby lenses were almost perfect: in terms of image quality, the ancient version was only slightly worse than the modern version. This is impressive, for this was a time where formalised mathematics had not yet calculated the perfect proportions of such a lens—the maker of the lenses must have used trial and error until perfecting this shape. The resulting lenses were thus not created by accident, nor by formula, but by dedicated mastery. This master craftsman could have brought the science of optics and refraction centuries forward if they had passed their knowledge on, but unfortunately, this does not appear to have come to pass. The Visby lenses are anomalous in this, indicating that the knowledge of their manufacture was apparently lost. It would not be rediscovered for centuries.

The origin of the lenses is still unclear. Because they appeared and then disappeared so suddenly in the Norse world, it does make this case a little more confusing. The presence of unfinished stones and raw material in the collection suggests there was some local manufacture going on, but did a Gotlander acquire the first lenses through trade (or loot!), later giving them to local craftsmen to modify and replicate? Had an Islamic or Byzantine craftsman travelled and settled in Gotland to ply his trade abroad? Or was Gotland home to a once-in-a-millennium master inventor who took all his secrets to the grave? The possibilities are many, and at the moment it is all a little blurry. Adding to the fact that some of the pieces have been lost, our best bet at the moment is to hope that more lenses are discovered in another archaeological excavation. Then perhaps a connection could be made.

Regardless of who made them and how they got there, we can still play the “what if?” game. What if the lenses had fallen into the hands of a curious tinkerer who could have reverse-engineered them and invented the telescope 500 years before Galileo Galilei built his own? What if old Norse astronomers could have observed our solar system and pinpointed our place within it at the twilight of the Viking Age? What if an entire field of science had an extra 500 years of discoveries to work with, or if our understanding of light refraction and light itself an extra 500 years of experimentation?

What if, indeed.

Today, pieces of the collection can be seen in the historical museum in Visby, or in the Swedish National Museum in Stockholm.

Featured image: necklace of lenses; photo by mararie (Wikimedia Commons).

Further reading

http://www.kleinesdorfinschleswigholstein.de/buerger/oschmi/visby/visbye.htm

About the author

Cindy Levesque

Cindy G Levesque is a biological anthropologist and archaeologist from New Brunswick, Canada. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of New Brunswick, and her Master of Science degree at Sheffield University in England. She currently lives in Uppsala, Sweden.